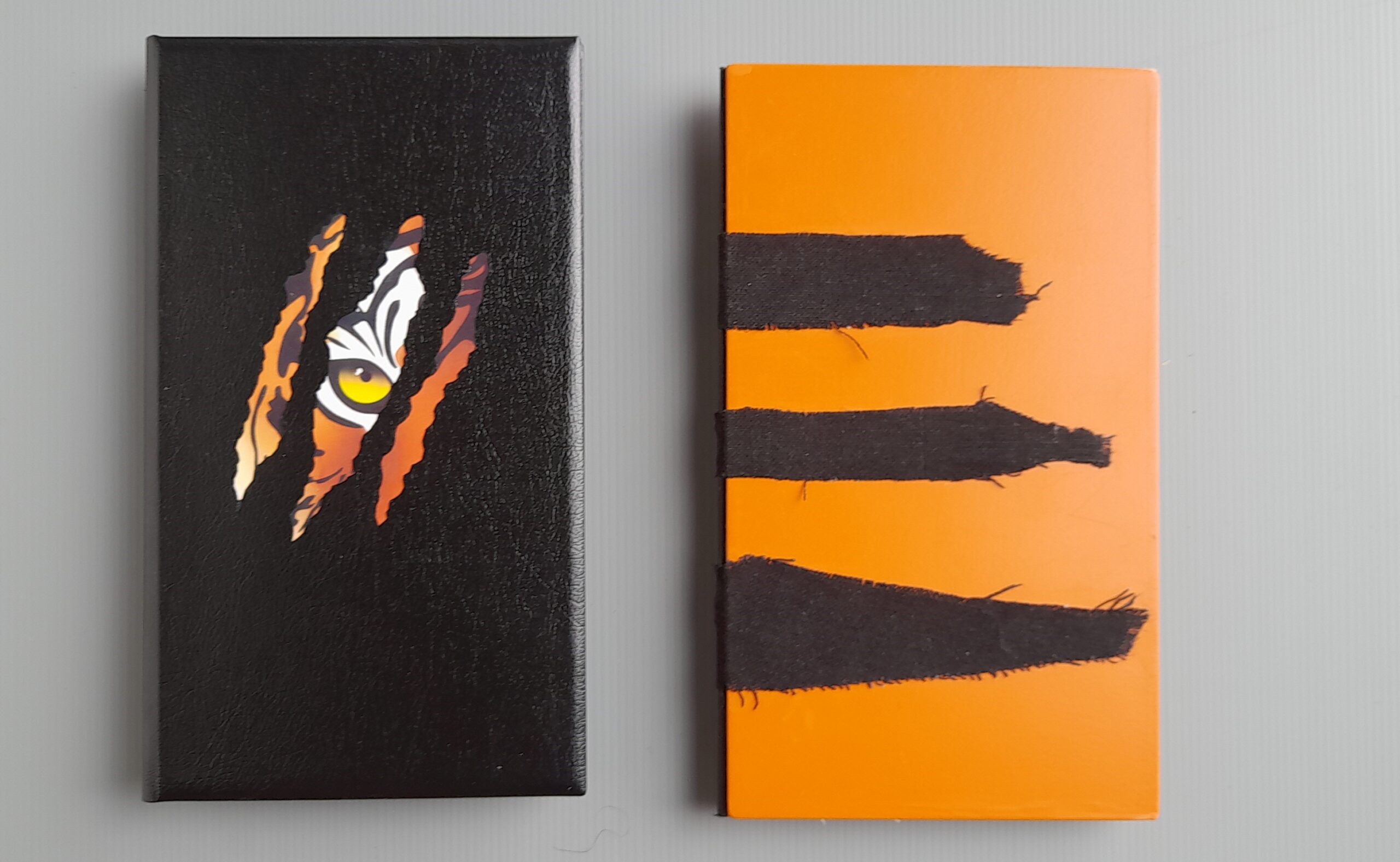

Top:

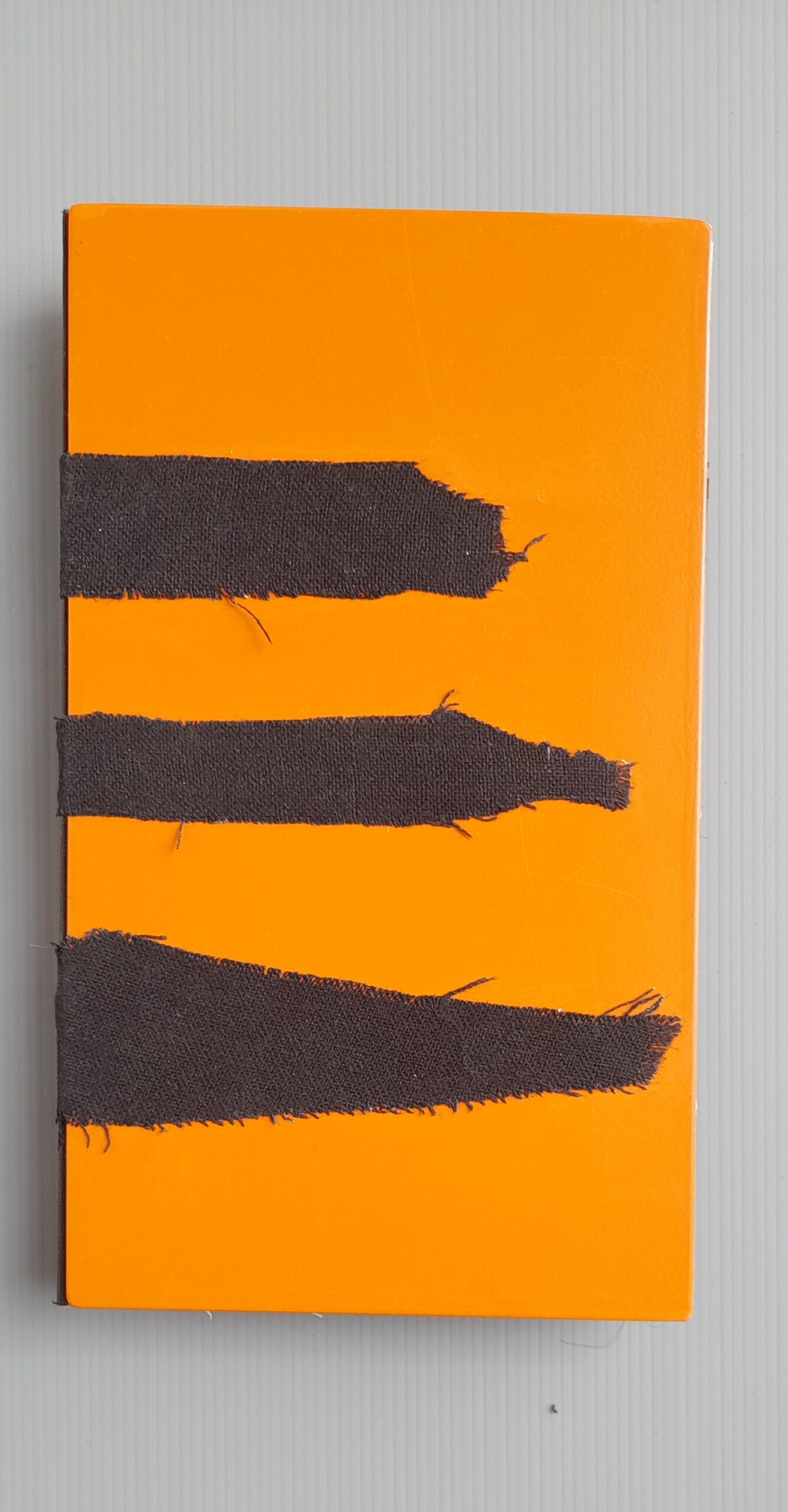

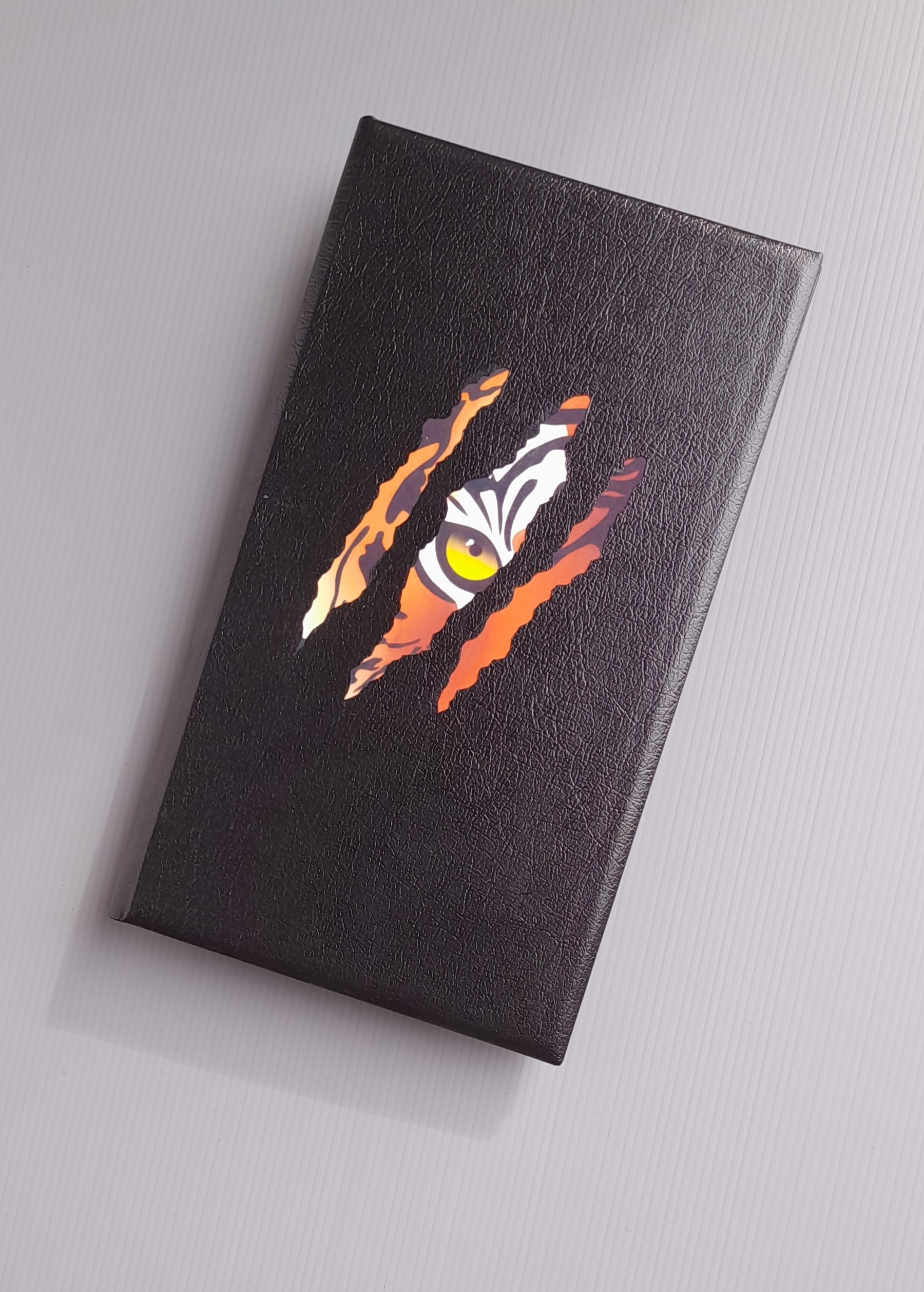

The pair of Tyger Twos.

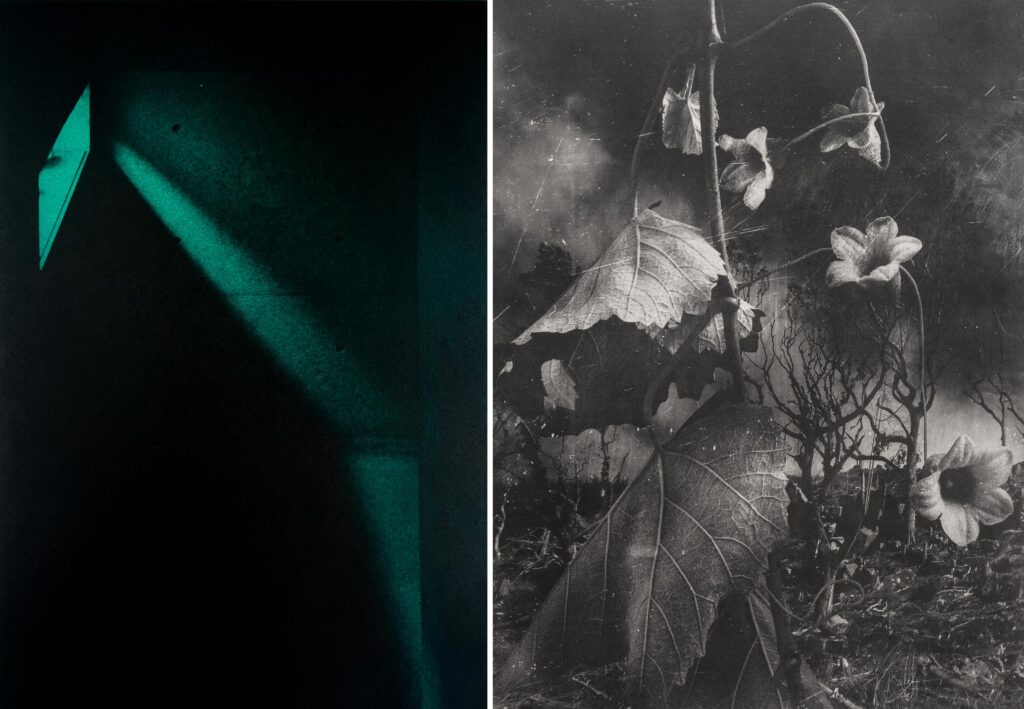

Below:

Paul Thompson’s version, Terrie Reddish’s version and a detail of Reddish’s work.

All images courtesy of the artists

New Zealanders Terrie Reddish and Paul Thomson consider their letterpress printed artist book, Tyger, to wrap up the big themes of religion, science and the history of the book. Their departure point was Englishman William Blake (1757-1827) who wrote, illustrated, and printed a series of little books that, while largely ignored in his time, are now extremely highly regarded and rare collectors’ items.

Depth of impression is usually a reference to the impressions that letterpress printing indents into thick paper. It gives that physically wonderful difference between hand printing with metal or wooden fonts and blocks and the smoother result of commercial printing techniques such as offset or digital printing. But in a wider and historical sense the term could easily be applied to the long period before the twentieth century when artist books became widely recognised as a genre in itself.

This conceptual legitimisation’s usual trajectory often starts with the deluxe ‘livres d’ artistes’ commissioned by French art dealers in the early twentieth century and featured name and bankable artists such as Max Ernst,Henri Mattise, Joan Miro and Pablo Picasso. Then with the impetus provided by the Italian Futurists and Russian Constructivists, handmade books entered the consciousness of the avant-garde. Subsequent twentieth century movements such as Dada, Surrealism, Fluxus, Conceptual and Women’s Art expanded the vehicle of the book as a consideration for ‘serious’ art practice. As this effervescence continued artist books ranged from works using high quality and traditional materials and fine crafting to photocopied and stapled multiples. A plethora of approaches and manifestations.

But for more than 1000 years before the twentieth century concept of the artist book, artists were producing works of art in the form of codices. They had very different motivations to our modern concept of both art for art’s sake and the artist as a talented and free-wheeling ego. The idea of the artist as the embodiment of individual creativity is relatively recent. Stunning, intricate, imaginative books were made in their thousands for religious reasons. Often made by clerics as well as in secular workshops the illuminated bibles of the previous millennium could be said to be the precursors of both illustrated books and the later comics and artist books.

These bibles, lectionaries, liturgies, psalters, testaments, apocalypses, canon tables, catechisms, brevaries, gospels and Books of Hours ranged from the huge requiring a lectern for use in church rituals and as demonstrations of wealth and power to the miniature as exemplars of personal piety. Some, such as Ireland’s Book of Kells, are now rightly regarded as national treasures. Even in Islamic societies which proscribed depictions of humans, exquisite calligraphy, intricate decoration and precious materials were used in the creation of Korans containing the message of the Prophet.

It’s a little like the historical analysis that posits the ‘great men’ of history (the great women of history were largely ignored) as the game-changers whereas now as in the old nature/nurture debate it is realised that context and happen-stance must be factored in as well. So, while the English poet, printer and artist William Blake as an apostle of the Romantic Movement could have claims to be the ‘founding father’ of the modern artist book their development is much more nuanced. Blake assisted by his wife, Catherine, created little coloured illustrated books. Many of these addressed Christian concerns while others were for children or promulgated his own views that imagination rather than dogma was the foundation for a meaningful life. He combined an anti-authoritarianism platform with idiosyncratic and innovative printing techniques to illustrate and then print his books. It could be said that he bridges the gap between the earlier illuminated manuscript and the twentieth century artist book, both are handmade and in the form of a codex.

As a poet Blake is probably best known for his hymn Jerusalem with it’s ‘dark satanic mills’ but another work that typifies his questioning stance is The Tyger (1794). Blake’s Tyger examines the theological complexity of why a supposedly benevolent creator would allow for pain and violence or more broadly evil. The idea of free will goes some way to explain or excuse but questions still hang.

The Tyger

Tyger tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings he dare aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of they heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread and and what dread feet?

What the hammer? What the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? What dread grasp,

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

When the stars threw down their spears

And water’d heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger tyger burning bright.

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

Blake was intensely spiritual even as he questioned the underpinnings and and religious practices of his day. One idea that was common across most denominations and sects was the idea of a Prime Mover who set the cosmos in motion and was responsible for all creation including the existence of current species. Reddish and Thompson’s Tyger revisions Blake’s question in the light of the subsequent and currently widely adopted mechanism of Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. What better response as a homage and an answer to Blake than as a hand-made book?

Tyger Two

Tyger tyger beast of chance

Fearful jaws appraising glance

Time’s patience without a plan

Sabre teeth, no fear of man

Silent approach victorious roar

Swift swift pounce all is gore

Genes and memes ride in tandem

Replications always random

The fear the scare entirely natural

Flight both learnt and instinctual

Cruel claws that rip, teeth that tear

The top of evolution’s stair

Man eats cow, tiger eats man

Just meshes in nature’s plan

Calorific survival demands such parity

Reality’s triumph over morality

Without the fear without the pain

Life’s stately progress makes no gain

Tyger tyger beast of chance

A prima donna in nature’s dance.

Terrie Reddish and Paul Thompson’s book is a collaboration. Blake composed his own poems and wrote his text based on his unique methodology and symbolism. He also prepared the plates and printed while his wife, Catherine, helped with the binding and perhaps also the colouring. Unfortunately, he sold very few although when one rarely comes up for auction they are now worth large sums of money. In his lifetime there were no institutions such as libraries, galleries and museums that have since expanded the market and that would have then included such items as idiosyncratic handmade books in their collections. The concept of an artist book is a modern one.

The two artists met when Thompson was a selector for a Print Council of New Zealand/Aotearoa touring exhibition of artist books and Reddish was a finalist. As both were passionate about artist books they discussed possible projects for a collaboration. Their thoughts ranged widely and they even made a dummy based on Borge’s Library of Babel story. But William Blake won out.

Their Tyger, a numbered and signed edition of twelve, is printed on 175gsm Revere Ivory paper with hard covers. The eight pages containing Blake’s original Tyger as it was first printed in 1794 and Thompson’s Tyger Two, editor’s comments, titles, dates and colophon were letterpress printed. All seems straightforward – another artist book and in this case an example of fine printing. But there is a twist. The edition comes in two very different bindings and this is acknowledged in the colophon. Reddish of Imprimo has clad her half of the edition in a fine and elegant way. There is a tyger’s eye peering through claw marks in the leather covers and the sewing and endpapers are an appropriate orange. Thompson has taken a more tygerish or muscular approach with tawny boards and heavy black fabric hinges mimicking the colouration and texture of a tyger’s fur. So while both books are single collector’s items, as a streak of tygers they complement each other.

—

Paul Thompson is captivated by all forms of the book. In addition to seven published non-fiction works, including two of poetry, he handcrafts artist books. museumphoton@gmail.com

Terrie Reddish is a bookbinder and letterpress printer who uses restored tools and vintage equipment to create unique artist books. pencilart@terrie-reddish.co.nz

—

Join the PCA and become a member. You’ll get the fine-art quarterly print magazine Imprint, free promotion of your exhibitions, discounts on art materials and a range of other exclusive benefits.