Christine Johnson: Recent works

In her new exhibition at the PCA Gallery, Christine Johnson’s latest works include those that celebrate pioneering botanist Eileen Ramsay, a woman whose fascination with plants has taken the artist on a decade-long journey. By Kate Gorringe-Smith.

30 October, 2023

In Exhibitions,

Printmaking, Q&A

Above:

Christine Johnson,

Eremophila (Emu Bush),

2023, pigment print, 41 x 31.5 cm.

NGV collection, commission for

Melbourne Now. Courtesy the

artist/National Gallery Victoria.

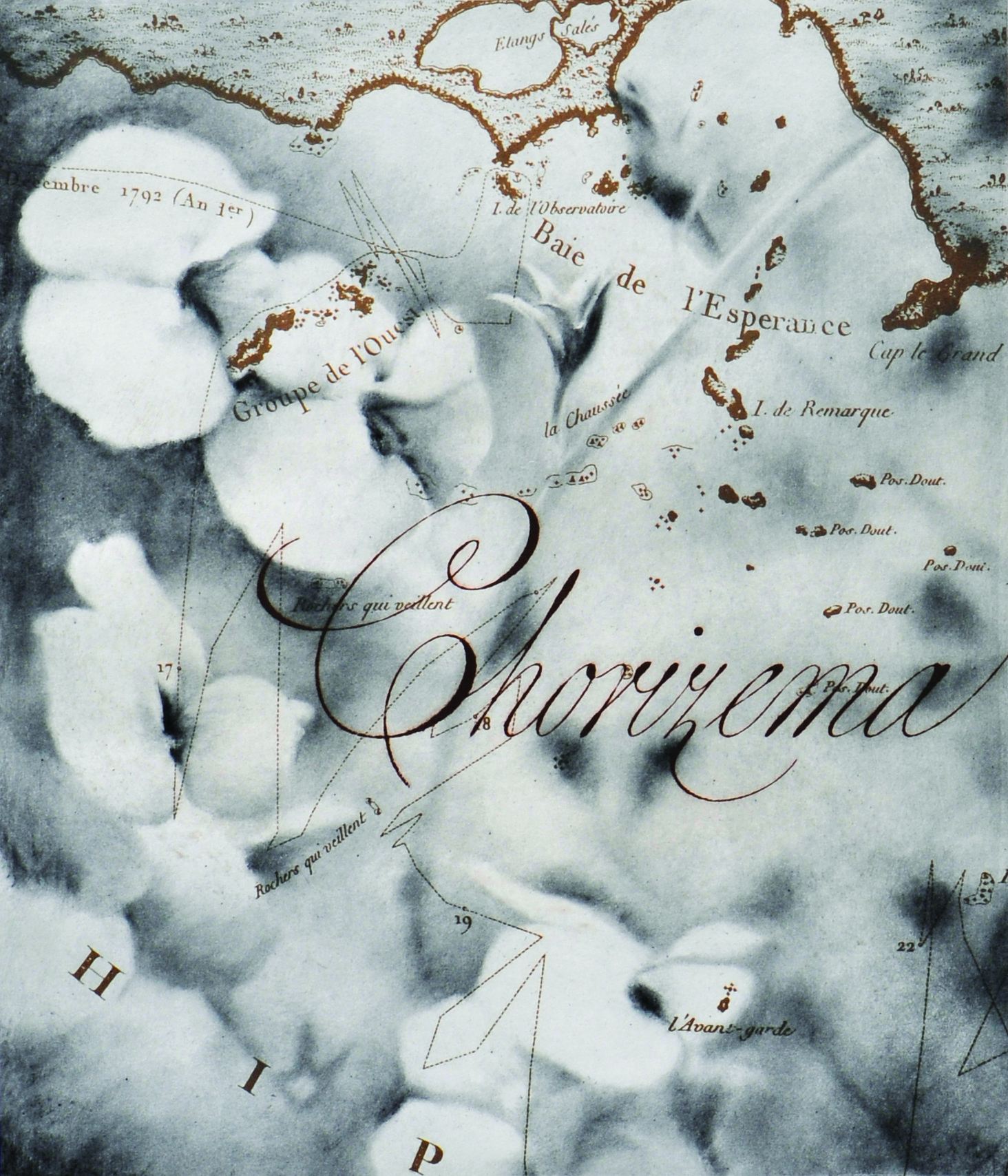

Below:

Christine Johnson,

Voyages Botanical, Chorizema illicifolia,

(Holly Flame Pea),

2014, solar-plate engraving, 34 x 29 cm.

State Library of Victoria. Courtesy of the

artist/State Library Victoria.

(Holly Flame Pea),

2014, solar-plate engraving, 34 x 29 cm.

State Library of Victoria. Courtesy of the

artist/State Library Victoria.

Christine Johnson in the studio, 2023.

Photography: Michael Shmith

Eileen Ramsay with fellow

naturalist John Plant.

Photography: Mary Chandler

Christine Johnson,

Acacia oswaldii (Umbrella Tree),

2023, pigment print, 41 x 31.5 cm.

For many years, plants have provided Christine Johnson with infinite ways to connect with the world. Recently she has spent much time in the north-west of Victoria becoming familiar with the endemic flora of that hostile environment. There, she encountered the story of Eileen Ramsay, and her involvement with the Sunraysia Field Naturalists Club, and the harsh beauty of the semi-arid Mallee. Johnson has been deeply drawn to its tough but humble plant life. ‘For me, the simple act of drawing deepens my contemplation of the miracles of nature. It is through nature we can find our place in the continuum of beauty and mystery that the first peoples of this country have always known.’[1]

Finding her passion for plants as a focus for her practice, which combines painting, drawing and printmaking, was not always a straight path. Hesitant to accept her own potential, but encouraged by high school art teacher Pip Stokes to study art, Johnson went straight from school to Caulfield Institute of Technology to gain a Diploma in Fine Art (Painting). She followed this with post-graduate studies in painting at RMIT and a Dip. Ed. Discovering that teaching was not her vocation, she became an art director, working on independent films and the burgeoning field of music videos. This was a formative time: creative, free and collaborative. But Johnson wanted more control over the work she was producing, and went back to life-drawing to reconnect with her own artistic vision.

At this time, Johnson lived in a flat in South Yarra, and her inclinations led her to the nearby Royal Botanic Gardens where she spent ‘many months wandering…in search of something—a subject, an idiom’.[2] Revelation came when she realised that she had found her subject and symbolism in the Gardens themselves.

Having grown up in a home graced with a garden by renowned Australian landscape designer Edna Walling, gardens had long been significant for Johnson. They provided ‘a refuge, a melding of self and environment’ she said when we met to discuss her work and her new exhibition, HER Story. Never particularly confident in her own artistic abilities, but encouraged by those who could see her potential, experimenting with the gardens as subject matter led Johnson to a turning-point.

‘I experimented with numerous approaches to painting and drawing… nothing felt right…until one day I painted a dark little smudge…of trees in the gardens at night. I was imitating Milton Avery’s abstracted landscapes. The edges were soft and merged. This was how I saw things, literally. My vision, myopic since birth, suddenly became a gift – I saw that everything was connected, a visual representation of my deepest belief and sense about life.’[3]

Johnson was also enamoured of another myopic artist, Pierre Bonnard who, she says, ‘made colours connect’ in his domestic scenes. This ‘released them from their subject, so that they had a symphonic unity’. The effect on Johnson was that, suddenly, the gardens held possibilities as a subject, loaded with symbolic meaning. ‘This was the beginning of a life’s journey towards looking, sensing, knowing, trusting.’[4]

The resulting body of work led to Johnson’s first solo exhibition, Ornamental Gardens, held in 1989 at Melbourne Contemporary Arts Gallery (MCA), a pioneer commercial art gallery on Gertrude Street in Collingwood. The exhibition featured paintings about horticulture and the formal art of gardens. Johnson became fascinated with both the shaping of nature and nature itself.

After the success of this exhibition, Johnson’s career path was set. She went on to exhibit once or twice a year at commercial galleries in Melbourne and Sydney. Her subject matter gradually came to focus on flowers as she created large lush canvases filled with heavy blooms, rich with symbolism, colour and light. Johnson says that her attention was drawn to the flowers she often saw growing in post-war suburban gardens, wondering about the link between pain, sorrow and beauty. ‘I was particularly drawn to the velvety richness of roses, and how their petals could filter and shape light,’ she says. ‘I found ways with layers of translucent paint to evoke the feeling at the heart of my intimate communion with nature. I was enchanted by the underlying wonder of reality. The flower paintings celebrated the glories of nature and are a meditation on the everchanging cycles of life and death.’[5]

Years of hard work brought Johnson commercial success and artistic acclaim, enabling her to survive as a single mother with two young children. But she was exhausted by the relentless pressure of exhibiting, and found the commercial gallery system’s demand for consistent work stifling. Experimentation was not encouraged. She craved the opportunity to take her work to new levels.

An opportunity arose in 2004 to hone printmaking skills that had been dormant since art school, when Port Jackson Press commissioned her to make a series of prints. It was an exciting opportunity to make professional-level prints with the aid of Melbourne printmaking luminaries Belinda Fox, Sophia Szilagyi and Trent Walter. This spurred desire for further change, to express her work on different levels and with intellectual rigour, to find ways to make work with a more direct historic/cultural context. Around this time Johnson heard that artist John Wolseley had been awarded one of State Library of Victoria’s inaugural Creative Fellowships. This program, which continues today, provides artists and scholars with an opportunity to explore SLV’s collections to support the production of new work. An idea took root.

In 2012 Johnson secured her SLV fellowship with the aim of blending ‘art with science, cartography, and excerpts from explorers’ journals to tell a story about the early years of European exploration of Australia by way of the flowers that were collected on the expeditions. Johnson viewed original illustrations by Sydney Parkinson, Pierre- Joseph Redouté, Ferdinand Bauer and others held in the State Library’s [rare books collection].’[6] In early 2013 Johnson attended a workshop with Silvi Glattauer at Baldessin Studio to learn the art of photogravure with which she realised the images for her SLV residency, culminating in the Voyages Botanical project, a touring exhibition comprising thirty solar-plate engravings and related drawings and paintings that were launched in 2014 at the Alliance Française, Melbourne, and concluded at Albury Regional Gallery, 2019. Johnson’s project led to the ongoing combined Creative Fellowship now offered by Baldessin Press and SLV.

The project was life-changing. The works that came out of it were a completely new direction for Johnson. During this time she had also moved from the leafy eastern suburbs to a house in Melbourne’s north with a garden full of scrubby native vegetation and raucous birdlife. She looked with fresh eyes on the subtle biodiversity of the endemic plants, and empathised with the colonial botanists who found a continent of remarkable, hitherto unrecorded, species.

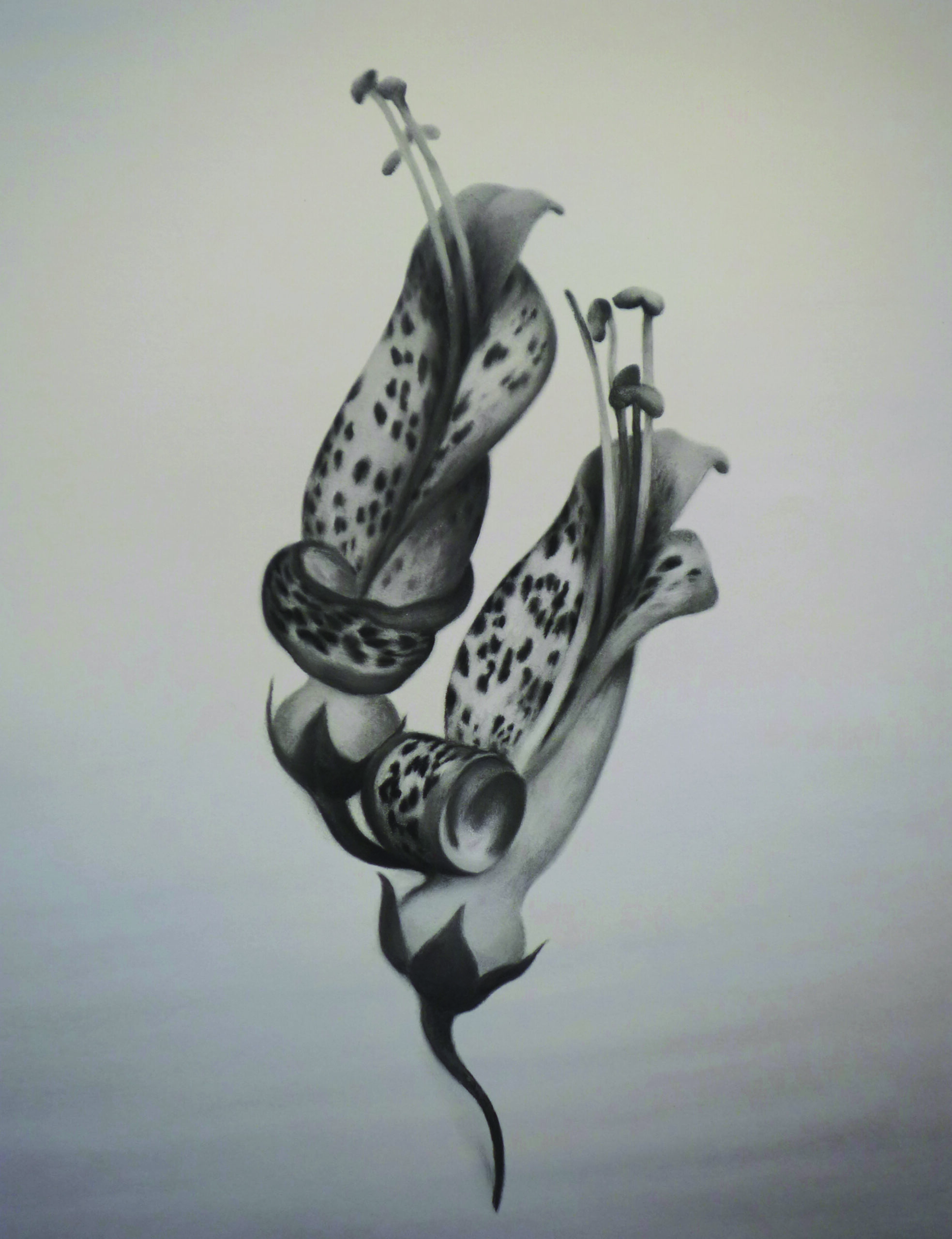

In stark contrast to her lush paintings, the prints of Voyages Botanical are soft and sepia-toned like parchment, with small areas of hand-colouring to enliven the subtle blooms. Although it took time to master solar etching, Johnson knew it was the ideal medium for her complex images using maps, text and flowers in literal and figurative layers. Her print Chorizema illicifolia layers a solar plate etching created from a charcoal drawing of the flower (the Holly Flame Pea-flower) with a map from Labillardiere’s voyage and an illustration of the plant by Pierre-Joseph Redouté.[7]

The SLV fellowship was followed by an invitation from Monash University’s Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences to work on a poignant project commemorating five young men who were victims of the First World War. Titled Five Soldiers: Untold Stories of World War One, the project marked the centenary of the armistice.

The five men, Alan Couve, Eric Bisset, Malcolm Jones, Wallace Jewkes and Frank Cahir, were studying at the Melbourne College of Pharmacy, the predecessor of the current faculty at Monash University, when war broke out.[8] Johnson chose a plant to represent each of them, moved by the notion that ‘the very history of pharmacy is itself botanical …the flowers are both symbolic of their link to the College of Pharmacy and are tokens of remembrance…In aesthetic terms, the wildflowers of the European battlefields when compared with those of Victoria’s regional areas are, however geographically or botanically divided, of delicate yet robust beauty, able to survive harsh conditions.’[9]

Following the shift in her practice initiated by her SLV fellowship, these images are also delicate in style and subdued in colour, emphasising the idea of flower as memorial. Johnson chose the floral emblems with care. Cornflowers, for example, worn by the French on Remembrance Day, link young Couve to his French-Mauritian heritage; Yellow Buttons grow in the Ballarat region where Bissett grew up; Austral Indigo is endemic to the Bendigo region of Jewkes’ childhood.[10] The exhibition catalogue contains photographs of the men along with Johnson’s detailed etchings of flowers printed over subtle backgrounds specific to each soldier—the cliffs of Gallipoli in one, the tracings of a handwritten letter in another. The flowers act as avatar for the individual, linking each back to his roots in Australian earth.

There is a beautiful and terrible parallel here between the anonymity of the fallen soldiers that the University is trying to address through this project and the invisibility of the plantlife Johnson depicts in such tender detail. The First World War remains Australia’s costliest conflict in terms of deaths and casualties: of the 416,809 men who enlisted from a population of fewer than five million people, more than 60,000 were killed and 156,000 wounded, gassed, or taken prisoner.[11] The humble plants chosen by Johnson as a memorial for each soldier stand as a metaphor for the vulnerability and fragility of human life and the anonymity of the thousands of dead. The individuality of each plant portrait belies this anonymity— each chosen both for its pharmaceutical significance and its ties to the lost soldier, each rendered in detail from an individual unique specimen. Johnson’s prints sit fluidly between the general experience of loss in war and the unique story of each soldier’s sacrifice, responding to these very specific but also universal tragedies with deftness and grace.

It was Alan Couve’s story in Five Soldiers that led Johnson to her current rich vein of research. The Couve family lost both their sons at Gallipoli, but a daughter, Eileen, remained, and went on to become a ‘little known but important botanist’.[12] Following WW1 there was a soldier settlement scheme in the Victorian Mallee, a notoriously dry and inhospitable area in Victoria’s north-west characterised by sandy soils and sparse scrub. After the death of his sons, Eileen’s father, Joson Couve, moved with his wife and daughter to Red Cliffs near Mildura to open a pharmacy and to assist returned soldiers.

In Mildura, during the tour of her Voyages Botanical exhibition, Johnson encountered Eileen Ramsay’s botanical collection, consisting of manila folders tied carefully with pink ribbon and filled with more than 1200 neatly labelled, pressed and dried plant specimens. She was immediately drawn to the aesthetics of the collection and to Ramsay’s story, intrigued by what it meant to engage with the Mallee in this way in the wake of her family’s tragedy. It is Ramsay’s story, and the work of the local Sunraysia Field Naturalists, that provided inspiration for Johnson’s exhibition, HER STORY: Mallee botanist, Hilda Eileen Ramsay.[13]

Ramsay joined a long lineage of women botanists in isolated areas who connected to the world through plants, for whom botany provided an acceptable way for participate in science and a field in which acute observational skills elevated the amateur to expert status. Johnson writes, ‘The plants in Eileen Ramsay’s botanical collection are endemic to Australia, having slowly evolved over millions of years but now, many of the species are under threat due to loss of habitat from land-clearing, mining, and farming…I am creating a suite of prints which will celebrate Eileen Ramsay’s life and botanical legacy. It will highlight a selection of the plants she collected and embody the rich historical and environmental narrative that surround them.’[14]

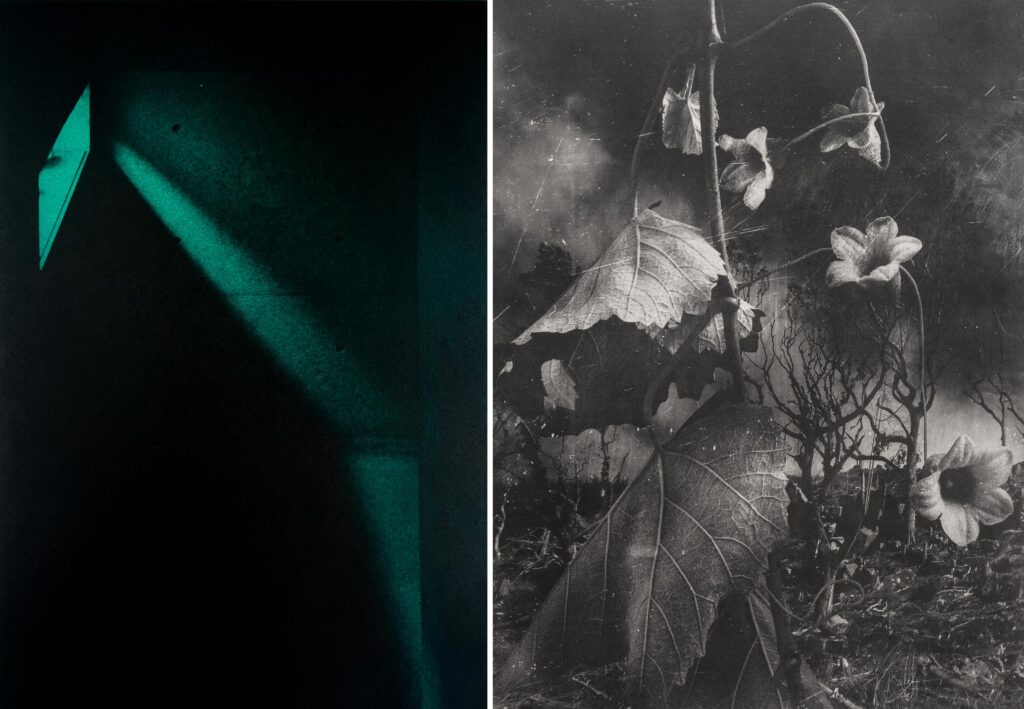

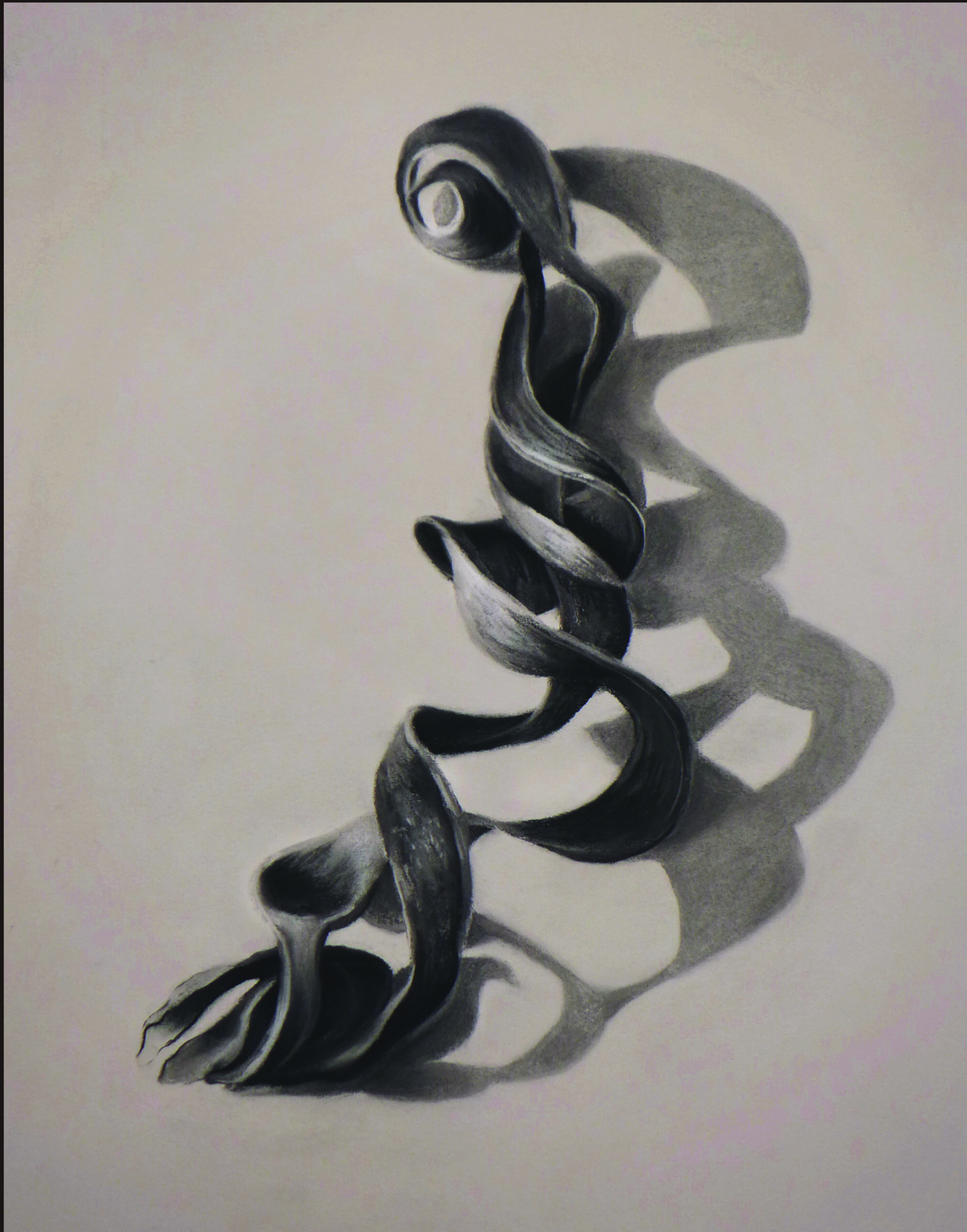

For this series, Johnson’s prints have again undergone a transformation, as she mostly works in pastel and charcoal. Like the notorious Mallee soil, these are ‘fugitive substances’ likely to float off with even the slightest gust. ‘However, by employing processes of reproduction, digital alteration and layering, the images have gradually developed and evolved and are further transmuted by combining intaglio and digital printing processes.’[15]

With this new exhibition, Johnson’s treatment of plants has similarly undergone a transformation. Rather than a conduit for emotional states or as human avatars, here the plants are living organisms in their own right. Through Ramsay’s passion to understand and document her local plant life and its role in actively creating the environment in which she lived, Johnson’s works acknowledge ‘that plants are living beings in their own right…[deserving] our attention for what that are, not [only] for what we can see reflected in them.’[16] The plants are the heroes: ‘…a call to be present, to keep something alive…to care.’[17]

—

1. Christine Johnson. 2023. Artist’s statement for Eremophila –

desert-loving plant.

2. www.christinejohnsonartist.com/blog

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Christine Johnson, email June 13 2023

6. Johnson, Christine, Voyages Botanical: Christine Johnson,

exhibition catalogue, 2014, 5.

7. Labillardière was the botanist on d’Entrecasteaux’s voyage to

Tasmania and WA in 1792-3, and in 1804-1807 published Novae

Hollandiae Plantarum Specimen, the most comprehensive

account of the Australian flora to that time; Pierre-Joseph

Redouté was one of France’s most famous botanical artists.

8. www.monash.edu/pharm/about/who/five-soldiersremembrance-

documentary

9. Johnson, Christine, Five Soldiers – untold stories of World War

One – Christine Johnson, exhibition catalogue, 2019, Fox Galleries.

10. Ibid.

11. www.awm.gov.au/articles/atwar/first-world-war

12. Christine Johnson, email June 13 2023.

13. Eileen Ramsay collected on the Millewa-Mallee lands. These

are the traditional lands of the Latji Latji, Hgintait, Nyeri

Nyeri and Wergaia peoples, whose deep knowledge and

understanding of the landscape and its lifeforms long precede

the work of Eileen Ramsay and her colleagues. Christine

Johnson acknowledges these peoples past and present.

14. Christine Johnson, email June 13 2023.

15. Ibid.

16. Aloi, Giovanni, Botanical Speculations: Plants in Contemporary

Art, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2018, xxiv.

17. Ibid., 9.

—

Kate Gorringe-Smith is a contemporary printmaker working on the lands of the Wurundjeri people. She is also the instigator and coordinator of the Overwintering Project: Mapping sanctuary.

www.overwinteringproject.com

—

Join the PCA and become a member. You’ll get the fine-art quarterly print magazine Imprint, free promotion of your exhibitions, discounts on art materials and a range of other exclusive benefits.