Gerhard Richter:

‘ATLAS: Overview’

at GOMA

Andrew Stephens discovers an enormous room at GOMA in Brisbane that offers a rare insight into the working mind of renowned German artist Gerhard Richter. Faccus eos ea doles audi dis aut fugiatur sequost ut quos vendis magnisin prae solorporest,

November 20, 2017

In Interviews,

Printmaking, Q&A

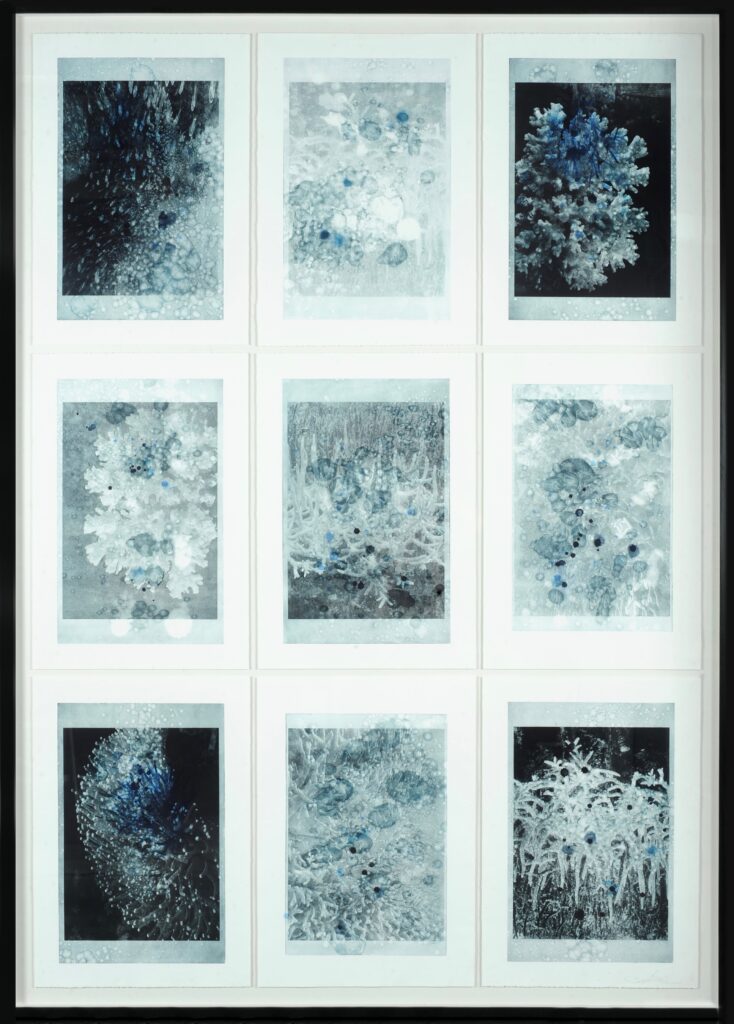

The idea of the ‘edition’ is something that Gerhard Richter has contemplated continually throughout his 50-plus-year career. In the book Gerhard Richter–Unique Pieces in Series, Hubertus Butin writes that in his painting editions, photographs, prints, drawings and multiples, Richter has developed various ways of variegating individual works in their appearance. While painting is his primary form of practice—hence the focus of the stunning new exhibition Gerhard Richter—The life of images at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art—Richter is also interested in showing audiences how he develops his ideas.

At the centre of this exploration is ATLAS, a collection of more than 800 panels of images that Richter has been archiving since the 1960s. First exhibited in the 1970s, this collection of photographs, press cuttings and sketches was arranged on loose pieces of paper. It incorporated family photos, Holocaust images, photos Richter has taken of landscapes and still-lives, and much if it has been source material for his paintings. Stored at Munich’s Lenbachhaus art museum, ATLAS has become too fragile to travel, even though it has been exhibited in part a number of times. To get around this, GOMA has managed to present ATLAS: Overview, a collection of about 400 images drawn from the original. It is, in essence, an edition—and Overview is an idea Richter applauds and has been heavily involved in curating. Curators Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow and Rosemary Hawker say they have been thrilled with the results.

Dr Hawker, a Senior Lecturer, Fine Art, Griffith University, says the extraordinarily high-quality reproductions of the original ATLAS are just a fragment of Richter’s encyclopaedic sampling of the images in his life in the 20th and 21st centuries. ‘Within that he has given us his sampling and refinement of the project,’ she says. ‘The fact that this is his edit of ATLAS is in some ways very curious. He has organised it and some of the juxtapositions are quite startling. Some of the imagery is quite confronting.’

Dr Hawker says the organisation of all these images is a circle from start to end, with some of the more confronting images at the start, moving through the family photographs and clippings and more easily consumed landscaped images. ‘Yet there is no way of describing ATLAS because it is so deeply based in diversity,’ Dr Hawker says. ‘It is so much about a view into Richter’s thinking. Some of the images have tape and paint and dirt on them: it is very much like an artist’s notebook.’

Because the original ATLAS is so large and cumbersome, galleries have in the past found it almost impossible to exhibit. Over time, some of the magazine clippings have yellowed and become brittle, even though Richter is a careful artist who monitors such things. As time has passed, the curators and conservators at Lenbachhaus have found it very difficult to deal with requests to exhibit it. ‘Nobody wants to display the whole thing because it is so enormous,’ says Dr Hawker, ‘but everybody wants a little bit of ATLAS for their Richter show.’

Thus the museum devised a large reproduction of the entire ATLAS and published it in a four-volume set. While Richter has decided that ATLAS itself does not travel anymore, GOMA managed to negotiate this new work, the edition called ATLAS: Overview. ‘This is the first time it has been shown and there is only one full edition in the world.’ While this edition will go on to show elsewhere, Dr Hawker says the original remains an organic work that will grow. ‘It was expected that Richter would put an end date on it but the still hasn’t done that. He can’t let go—which is good for us.’