Top:

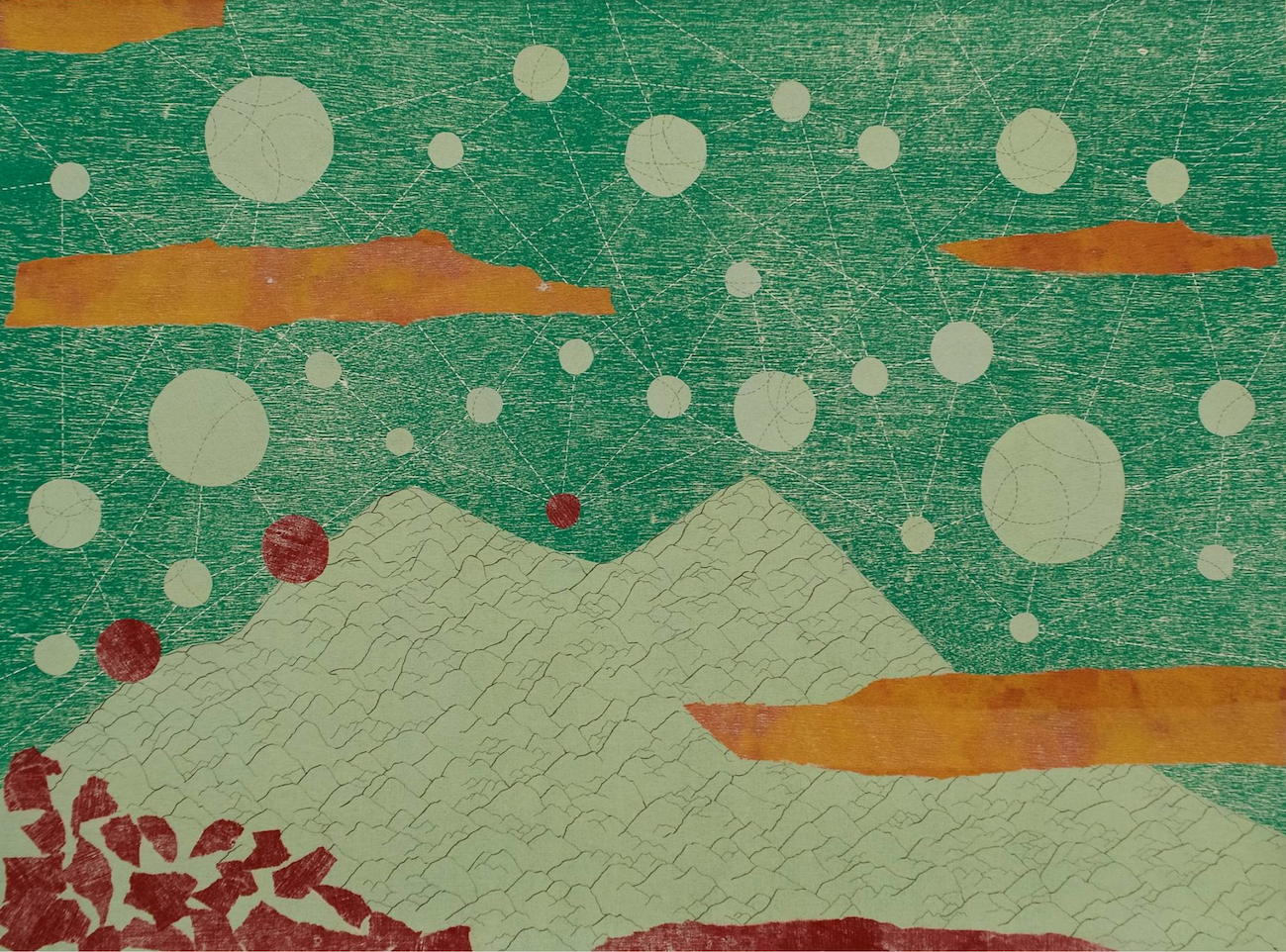

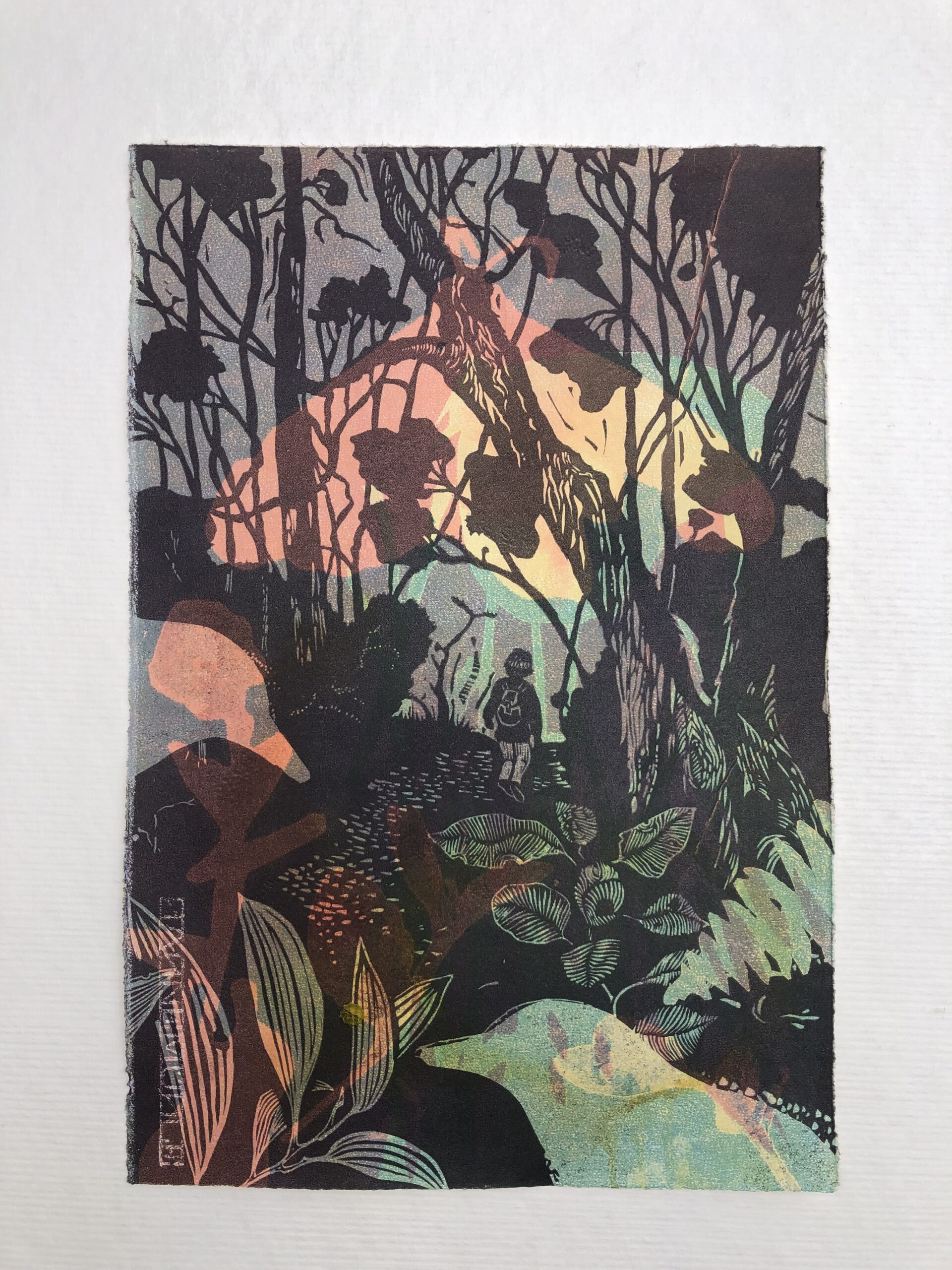

Jessi Wong, Across the universe XIX, 2023, woodblock collage and pen on paper, 56 x 76 cm, unique state.

Jessi Wong

Jessi Wong’s arts practice favors pattern and repetition referencing organic forms found in nature – stars, woodgrain, striated rocks. These artworks explore uncharted journeys using color, pattern and cartographic influences. The organic shape of the torn paper references the natural world juxtaposed with composition, imposing order amongst chaos.

Composition, color, and layering play a structural role in her visual language. Combining woodblock, lino, collage and pen, her artworks challenge perceptions of replication and traditional printmaking.

Below: Jessi Wong with works in progress

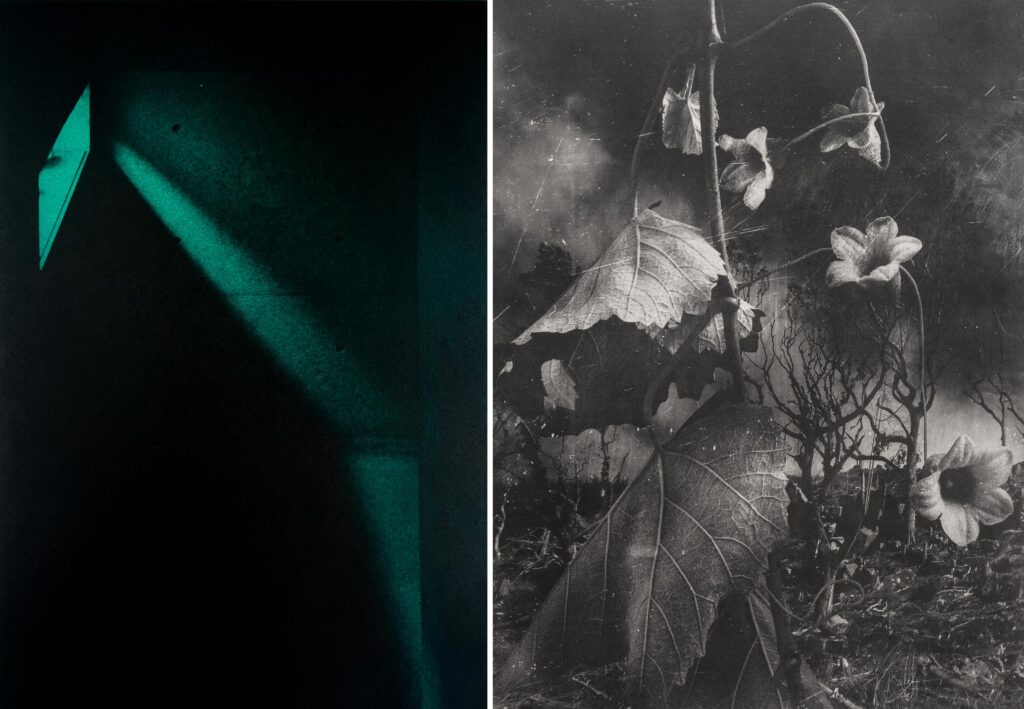

Helen Kocis Edwards

Helen Kocis Edwards considers the notion of Biophilia, our inherent capacity for human-nature relationships, through imagery reminiscent of story books and fairy tales.

Native flora and cutout stencils from discarded plastic combine within monoprints on paper to explore this interconnectedness. Each element is moved around and layered to create a dialogue. Scale, placement, texture, form and color are manipulated allowing organic interactions to evolve.

The work explores the complex and symbiotic connections of living creatures and plants within physical and emotional landscapes.

Kocis Edwards (MFA) has a studio with Jessi Wong and Andrej Kocis at Artery Co-operative Northcote Melbourne where she is also a Director.

Below: Helen Kocis Edwards, Wandering Wondering, 2024, artist book, monoprints with stencils and leaves on Magnani Aquarelle paper, Image and paper 18cmh x 14cmw x length variable, unique state.

Alexis Beckett

Our love of living things/nature can spill over into love of imitations of living things. We have been decorating our possessions, our homes and our bodies with designs inspired by nature for centuries. In the contemporary context of an expanding human population and corresponding loss of other species and wild spaces, will the absence of nature in our daily lives be satisfied by plastic ( imitations ) of nature? This idea is explored by making a collection of plastic plants and plastic sheets then inking them up and printing them, referencing the plant collections and prints so popular in Victorian times.

Below: Alexis Beckett: works in progress

Nicholas Chilvers

The Lizard Slayer enacts a human hybrid identity blended with a lizard. Given the “chimera” can be viewed as a living entity whose body is composed of genetically distinct cells from another body, my expressions represent both lizard and human parts. Hybridity is considered through Bataille’s argument that eroticism is an expression of a fundamental link to nature. Queer fetish culture can express a similar sensibility by emphasizing desires that are often considered animalistic (bears, otters, pigs, etc.). This multidisciplinary artwork investigates this concept as a life-force strong enough to dissolve boundaries between the human self and greater ecology.

Below: Nicholas Chilvers, The Lizard Slayer, 2024, photo document of performance, latex hood, shiny shorts, Giclee prints on paper, Size variable, unique state.

Kate Gorringe-Smith

In her Riverwork pieces, Kate Gorringe-Smith juxtaposes the common urban building materials of clay and glass with the fragility of native plants found beside the Yarra/Birrarung. The plant forms emboss the clay, accentuated by melted glass. A collaboration between the artist and the riparian environment of inner Melbourne/Naarm, this work looks toward future urban landscapes designed to restore, preserve and enhance the needs of both human and non-human inhabitants of the planet.

Below: Kate Gorringe-Smith, Riverwork pieces (10 pieces altogether), 2023, embossed clay and glass, each 20 x 8 x .5 cm, installation dimensions variable, unique state.

Andrej Kocis

‘If you look with different eyes…’ is a series of interactive prints exploring the relationship between urban animals – owls – and the built environment. The prints contain illustrations of high-rise buildings, typical of any major CBD. By using a smart device to scan each print, a three-dimensional image of an owl is revealed, superimposed on each central building. In this way, looking with different eyes reveals a conflict we all feel about this relationship but don’t often see – reverence for the owls but also sorrow for their concrete confinement.

Below: Andrej Kocis, If you look with different eyes #1, 2024, interactive giclee print, image 28 x 26 cm, 1/10.

Athena Lim Malamas

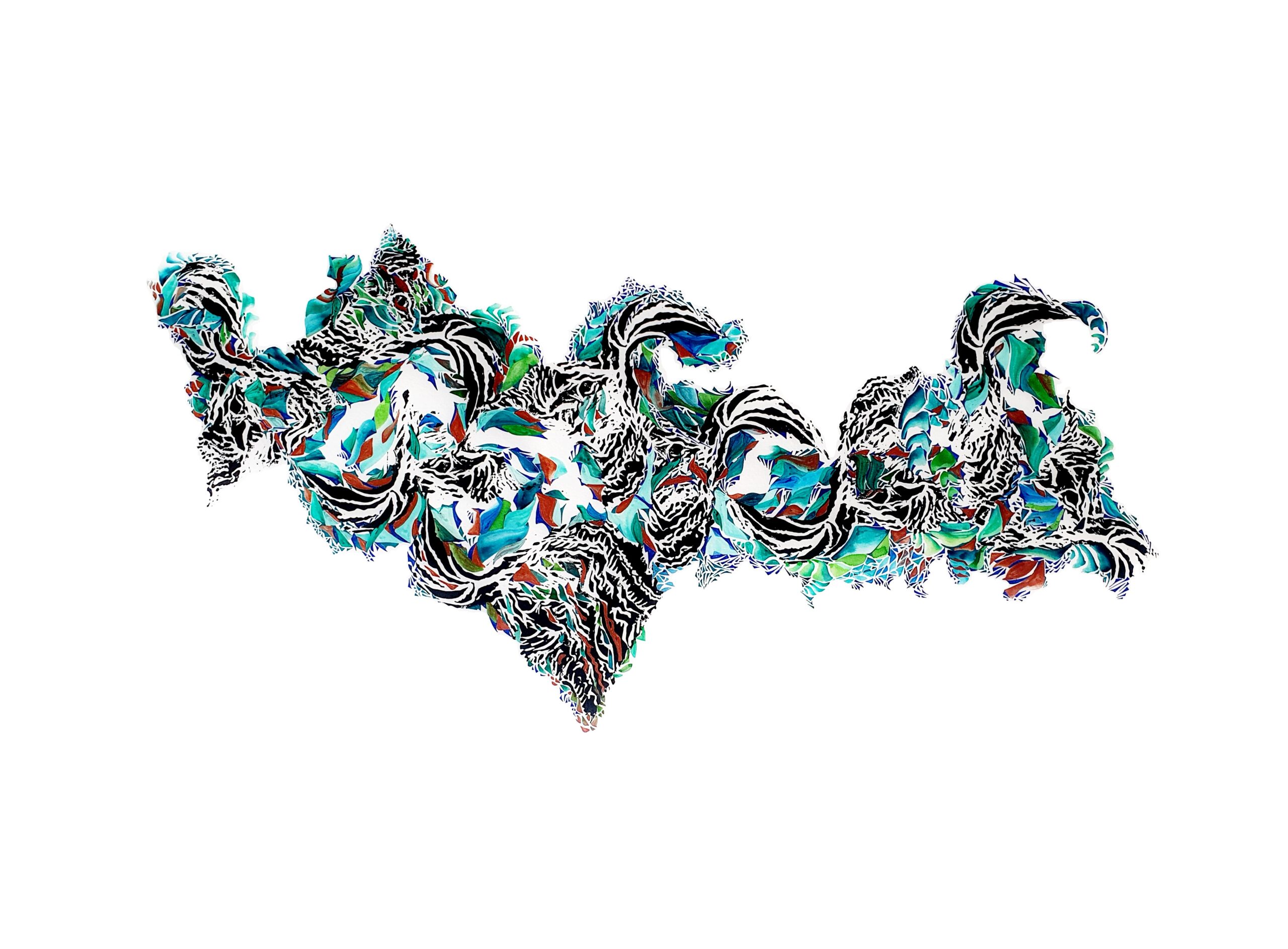

Much of my recent work has seen me fuse my repeating linocuts with other mediums, predominantly ink and acrylic. It continues to be an exploration of duality and dependence – the reliance of color upon shape and form and vice versa. The term Biophilia succinctly captures an element of this relationship and highlights a prevalent theme that is often woven into my work: abstraction representing the emotional and the external tied to capturing inspiration from nature and its elements. Creating for this exhibit was particularly enriching because it gave me a new framework for understanding my own creative process by allowing me to define some of the relationships within my work in a more concrete way.

Below: Athena Lim Malamas, Flight Through The Whirlpool II, 2023, mixed media: linocut, ink, enamel, 100 x 70 cm, unique state.

Helen Timbury

My work is about the remnant bush areas I am drawn to when I seek the outdoors. These places are becoming increasingly valuable to me as housing development builds up around my peri-urban hometown of Drouin.

In summer at dusk, I walk to my street’s end to see flying fox silhouettes around the remnant eucalypt growing metres from the V-line tracks. On a damp May Saturday I can find myself anointed with birdcall and the scent of leaf litter on a bush track 20 minutes drive from home.

I hope for the survival of these restorative tracts of wild bush sandwiched between farmland and new housing development, road and infrastructure.

Below: Helen Timbury: works in progress.

Rebecca Young

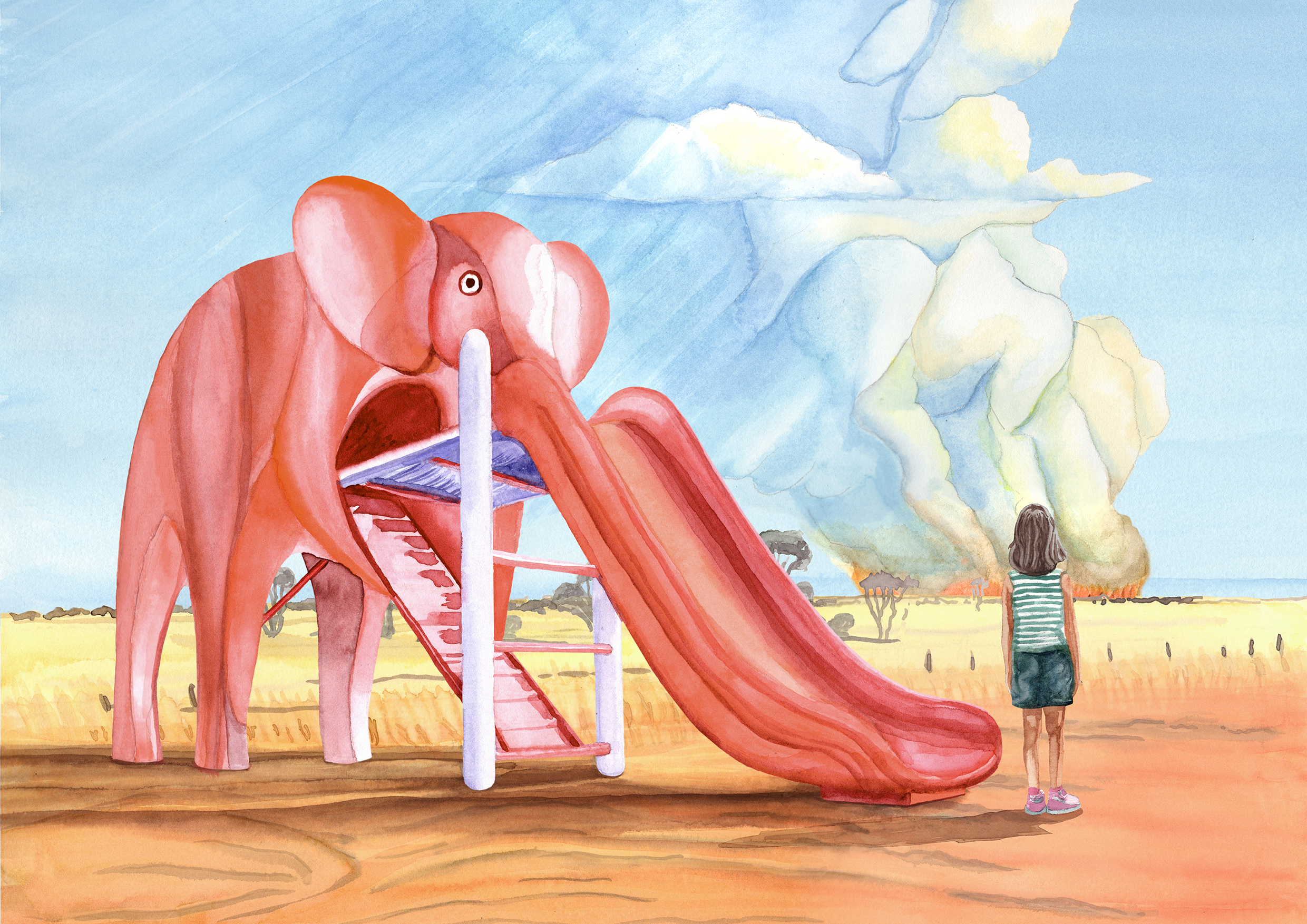

Below: Rebecca Young, Pink Elephant, 2024, giclee print, image size: 42 x 29.7cm, 1/100

In its most common accepted meaning, ‘biophilia’ is about human experiences with nature, but it is also about design and conservation. Biophilic design principles in architecture and urban planning emphasise features, forms and patterns that reflect the environment: vegetation, water, animals, light, air flow, scents, and sounds. The interplay between elements in an environment have multi-layered and reciprocal influences on the well-being of people inhabiting a shared space. The concept explores human relationships with natural elements within an urban context to consider the importance of restoring and preserving native habitat and species, and to encourage the instinctive need humans have for this type of connection. Or this is what I’ve been told; it all sounds rather wishy-washy to me.

I was recently asked about the term biophilia, and I immediately thought of Baroque art, even though it is not a Baroque concept. I have been told that the term was conceived much later than that, in the 1980s, by biologist and conservationist Edward O. Wilson. That makes biophilia a very modern idea; but a winsome idea that can be quaintly applied through modern eyes to art history, with Humanist sensibility. Wilson’s hypothesis proposes an evolutionary impulse to seek meaningful encounters with the natural environment. We need to be ‘in nature’ as much as possible, according to Wilson, because we have evolved as part of it, and we are part of its greater ecosystems.

But to me, ‘philia’ is a slippery suffix. It connotes eroticism and fetish, and perhaps pernicious fascinations with human and non-human encounters. What I have discovered is that Wilson did not invent the term, “biophilia”. It was a German psychoanalyst named Dr Erich Fromm in the early 1970s. Fromm’s thesis, The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness,[1] investigates human encounters with nature; his interest however is in the human propensity to do harm, and to be destructive in the world and to the environment.

Fromm links Freud’s notion of ‘necrophilia’—a love of death and destruction and a proclivity to make love to murdered corpses—to his concept of the death drive; and he offers ‘biophilia’ as a dialectic opposite. Necrophilia represents more than a sensational idea—. The necrophiliac impulse is a symbolic expression of a desire to control and possess, and to do so to the point of restricting life or directly causing and venerating its ending. According to Fromm, “destructiveness” is different to any other form of protective, defensive, or aggressive behaviour that serves an evolutionary purpose. It is a distinct human trait and a malevolent psychological state. By likening destructiveness to necrophilia, Fromm aimed to highlight the inherent contradiction between a genuine love for life (biophilia means love of life) and the destructive tendencies ever present in human nature.

Take Caravaggio’s painting, Ragazzo morso da un Ramarro (1596) as an example of an excellent “biophilic” artwork in that sense—it’s the one with a pubescent boy bitten on the finger by a lizard. The gorgeous youth recoils with horror, jumping back with tiny lizard teeth still incising his fingertip. The creature poses no threat to the boy, but we know it is the lizard who is in danger as he may soon be crushed unless the child takes mercy. The question is, will “nature”—that is, the human nature and the natural character of the boy—cause a violent reaction that kills the little creature, or will he show empathy? There are two strong forces at play within the boy’s developing psychology: An urge to control and an impulse to care.

The symbolism is drawn from ancient poetry. Roman poet Marcus Valerius Martial writes:

“Spare the lizard, treacherous boy, creeping toward you. It desires to perish between your fingers”.[2]

The poem describes a Classical bronze statue by Praxiteles, Apollo Sauroktonos, (the Lizard Slayer). Praxiteles’ sculpture shows Apollo, naked, aged somewhere between boyhood and manhood, coquettishly taunting a lizard, grasping at it as it clambers up a tree. He leans against the trunk and tilts his head, investigating the terrified animal. His stance emphasises his counterpoise, his confidence, and control, while the lizard’s fear charges the scene with frisson. The masturbatory undertones may be apparent to some—it is easy to imagine how the reptile will wiggle and fight in his palm as the life is squeezed out of him by a reckless teenager in search of misadventure and pleasure.

In ancient Greek language, “philia” refers to the type of love you find in long-term friendships, in caring for children or pets, or the kind of love you find in the garden as you wait for springtime. Eros, on the other hand, is a type of love associated with passion—passionate love and eroticism—the kind that takes risks, shoots and spurts without thinking. Philia represents a far more sustained mode of tenderness while eros drives people to seek pleasure, and to procreate. But eros can be destructive without philia’s balancing affect. Philia reduces the tension between erotic impulses and the careful cultivation of intimacy. Yet sadly, since Freud, we have started to associate the notion of eros negatively with sexual transgression, and philia is relegated to the realm of “paraphilia”—the Modernist vocabulary for unhealthy fixations and sexual problems.

But this still situates the subject in the middle of an entirely Humanistic and individualistic worldview. Posthumanism on the other hand challenges the Humanist understanding of what it means to be in the world. Timothy Morton explores the implications of climate change from this post-humanist perspective in his book Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence. The book examines the interconnectedness of humans and nonhumans in the context of ecological crisis. Morton commandeers Theodor Adorno’s concept of non-identity thinking, which questions the idea of fixed identity and emphasises the importance of recognising the fluidity and contingency of collective subjectivities. Morton sees non-identity thinking as relevant to posthumanism and ecological thinking because it encourages us to move beyond rigid identity categories, and to engage with the entangled, interconnected nature of living within ecosystems.

[1] Fromm E. (1973). The anatomy of human destructiveness (First). Holt Rinehart and Winston.

[2] Jenifer Neils, “Praxiteles to Caravaggio: The ‘Apollo Sauroktonos’ Redefined.” The Art Bulletin 99, no. 4 (2017): 10–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44973215.

—

Biophilia is at the Print Council of Australia Gallery, printcouncil.org.au, 19 March-12 April, opening reception Thursday 21 March 5-7pm

—

Join the PCA and become a member. You’ll get the fine-art quarterly print magazine Imprint, free promotion of your exhibitions, discounts on art materials and a range of other exclusive benefits.