Sea Sings, Lumen and Wings Realm

The latest exhibition at the PCA Gallery positions print at the centre of idea-making, writes Dr Clare Humphries.

7 August, 2023

In Exhibitions,

Printmaking, Past Exhibitions

present, in place and time

On the surface, Sea Sings, Lumen, and Wings Realm is an exhibition of works that unapologetically use printmaking to realise ideas. The centrality of print is underscored by the location of the exhibition at the Print Council of Australia Gallery.

Yet, as I sit to write this exhibition essay, I find myself thinking about drawing.

Drawing is interwoven through the warp and weft of the exhibition. It is the means through which each artist has tried to record, to decipher, and to come to terms with their place on the Australian continent, and also their moment in time. In each work drawing moves in and out of relation with other media too. The momentum of activity in the exhibition crosses from one process into another, and back again, with drawing, photography, and printmaking brought into relationship with one another.

I have often thought that to draw is to make contact. A drawing, like a print, indexes a duration of touch. It may register the drag of charcoal across a surface, or the tap of a pencil as it stutters over a page. A line worn into a field of grass remembers the weight of two feet as they pressed, one-after-another, into the ground. And even a fleeting sketch of light made as a hand trails a torch through the air, still brings things into contact as the body travels through invisible and odourless gases. In each instance, the drawn surface is exposed to an inscriptive force (or the air to a disturbance), which registers a trace of presence in time.

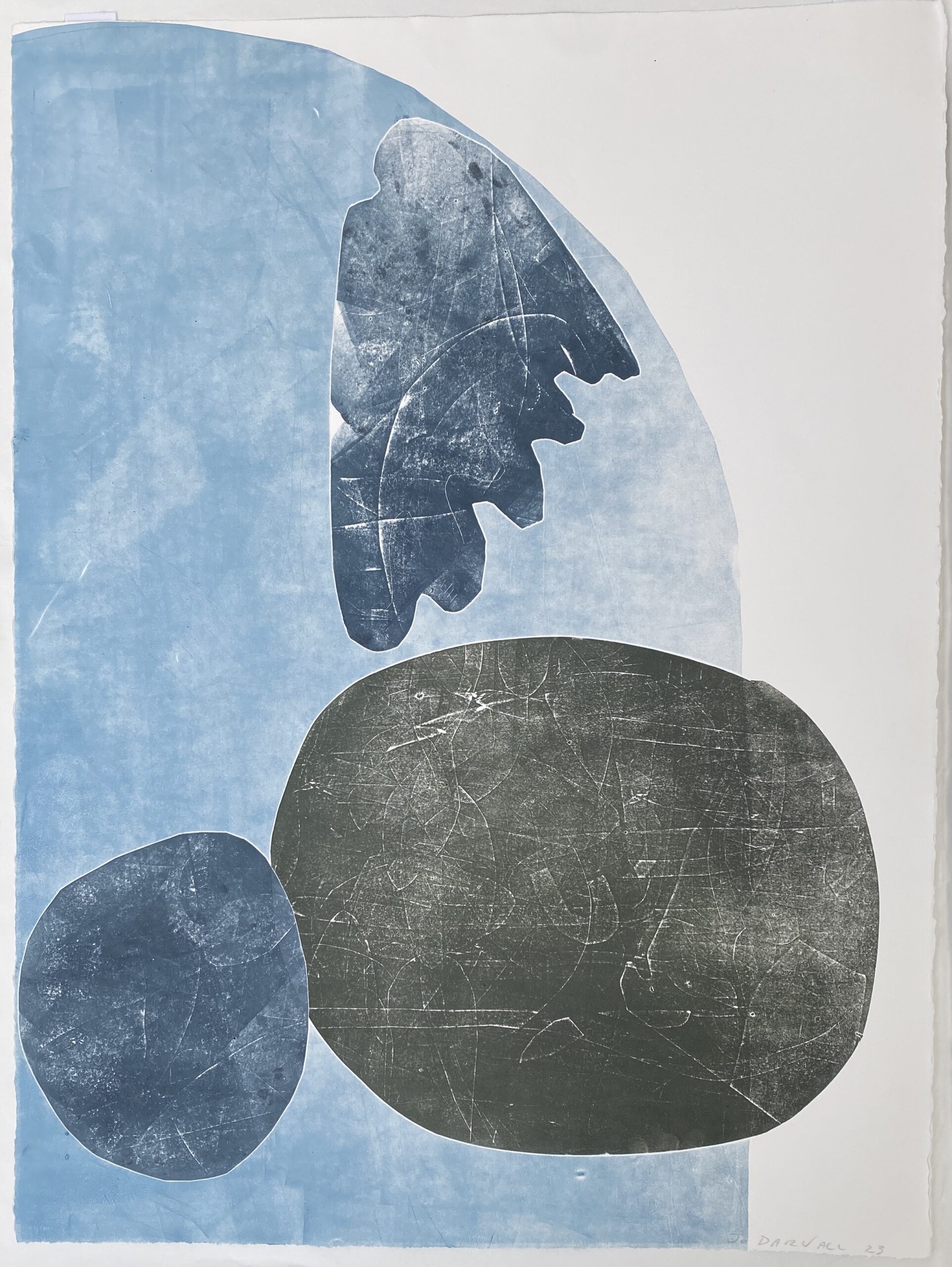

Drawings are suffused with indexical traces. Each mark arises in a passage of activity where moments of touch stage a relationship between a body[1], an action, and a receptive surface. In Jo Darvall’s practice the action at play is not just the physical gesture of drawing, but the act of careful attentiveness that initiates her gesture in the first place. Much of Darvall’s work is grounded in her ongoing method of walking, observing, and transcribing: wandering through forests, meandering along coastlines, as she notes down forms, and draws passages that enliven her senses.

In Ravuka Point, Yadua Fiji, from the book Hydrosphere (2023), scratches and dots show the path of Darvall’s vision as it brushed across clusters of vegetation, and skimmed stretches of shallow water. Breathlessly light marks reveal her soft gaze as it traversed the shore, whilst deep, pressured lines betray an intensity of attention given to the shadows. Notably though, we see no evidence of revision. Darvall made Ravuka Point by drawing directly onto an aluminium lithographic plate whilst on residency at Lancaster Press Fiji, a process in which erasure is not possible. Once a mark is made, even in error, it cannot not be undone. Plate lithography intensifies the immediacy of the drawn mark, and calls on the artist to be fully present in the moment. Darvall had to draw without looking back.

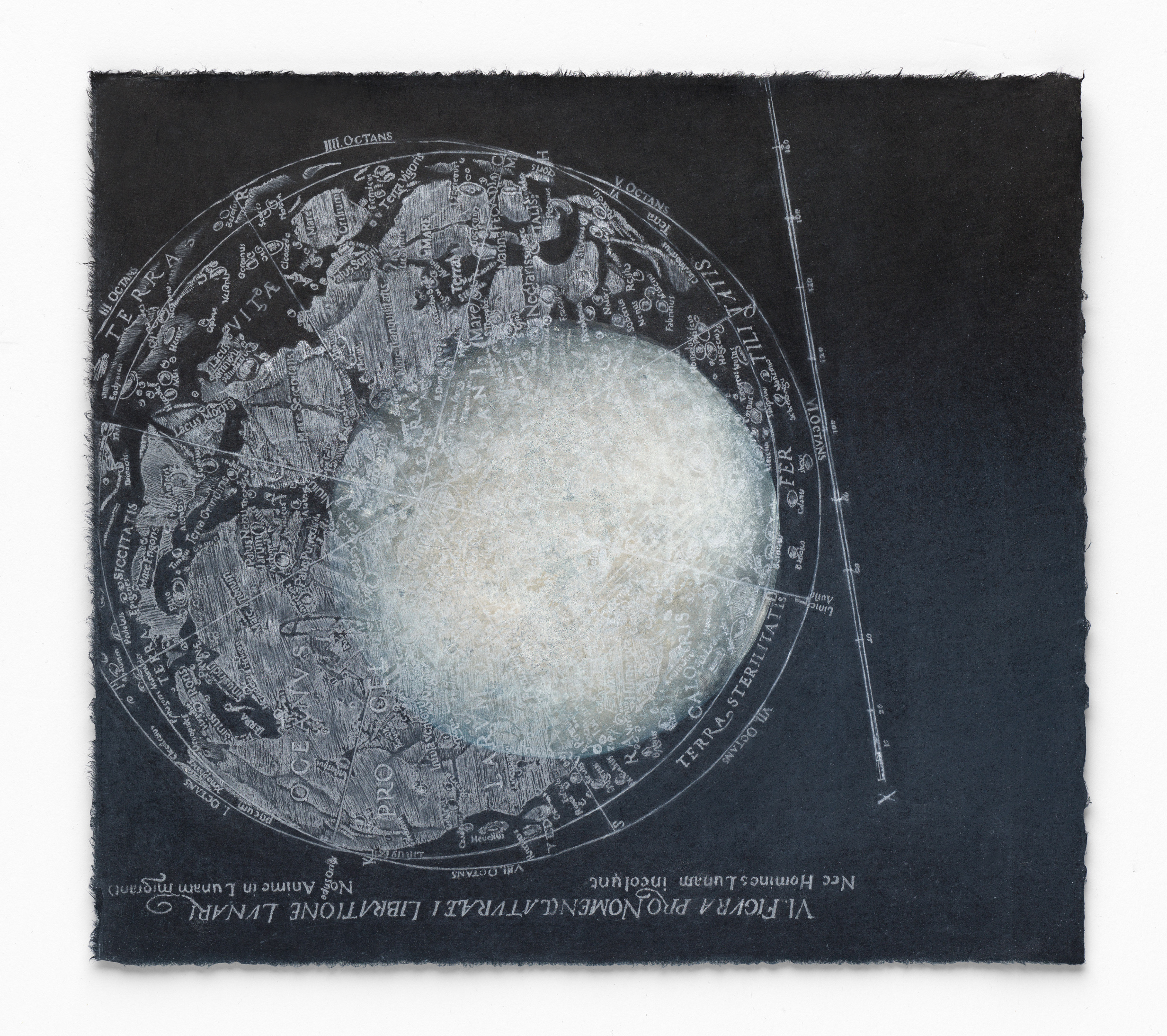

Where drawing is an evidentiary mark in Darvall’s practice, it assumes the task of re-visioning in my recent works in the exhibition. My latest project reorients celestial maps of the 17th Century, highlighting the ways early telescopes helped to imagine the skies of Terra Australis Incognita (Latin for ‘Unknown Southern Land’) as upside-down. The European notion of an inverted Australia is reflected clearly in the idea of the Antipodes (Latin for ‘with feet opposite ours’) which positions the Southern Hemisphere in reverse. The map of the moon by 17th century astronomer Giovanni Riccioli[2], for example, describes an upright position only for the Northern eye.

In Seas of Delirium (South Side Up) (2023), I incorporate an image of the rising moon made from my observations on the Western Coast of Australia. Over this intimately abraded surface I have enlarged and re-transcribed Riccioli’s map, rotating and flipping his ‘data’ to articulate a Southern position. In Perspectus Australis (with feet opposite) (2023), I undertook a similar inversion, upending segments of a print from Francis Place’s[3] series Vivarium Grenovicanum (1676). I specifically quote Prospectus Australis which presents a view from Greenwich Observatory looking South, locating the viewer close to what would later become the prime meridian[4] looking outward toward a picturesque unknown.

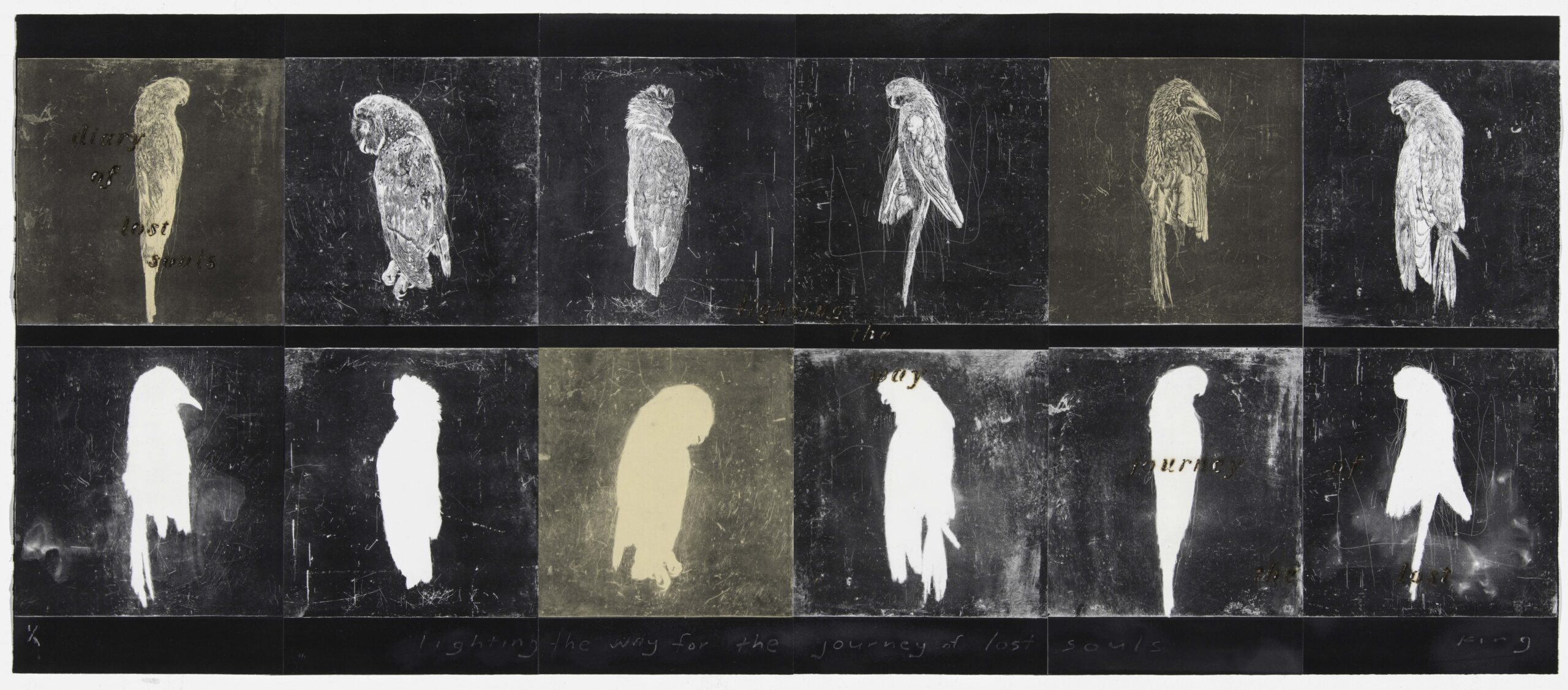

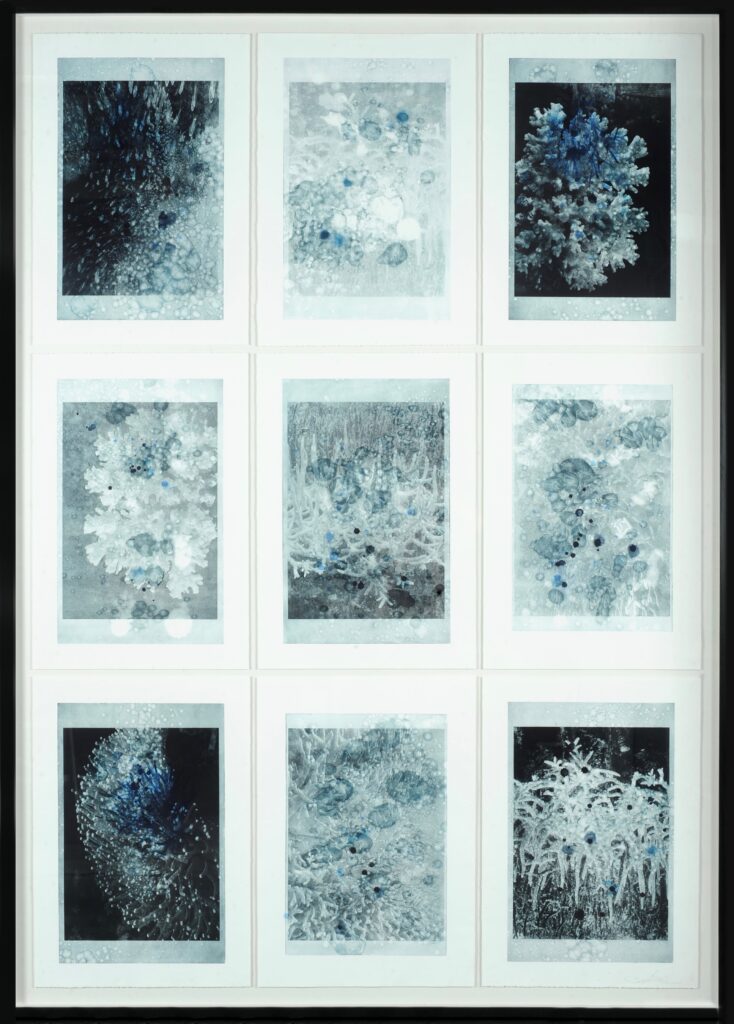

Martin King’s work also takes up the possibility of revisiting the past, yet his acts of transcription do not revise history. Instead, they call into question our present moment. In pages from the diary of lost souls (2022) King gathers a cacophony of photopolymer gravure etchings, captured photomechanically from sketches in naturalist John Cotton’s[5] sketchbook. The ghostly forms of Cotton’s birds are printed on parchment-yellow paper, forming a background of pages upon which the silhouette of a large tree is imprinted.

The tree in King’s work is an imagined hybrid of two species, an English Ash and a Peppermint Gum, that live in Melbourne’s Fitzroy Gardens, an urban park established in 1848 when Cotton was filling his book. There is a sense of the pressure with which the tree (an etching printed with force) has penetrated the pages beneath, grounding the spectral presence of Cotton’s birds that might otherwise float or fly off the page. It is under this strain of compression that the divided form suggests a force of colonisation over Australia’s ecologies. Yet, hope also arises: King’s tree emerges from the labour of slowly etched and hand-scored lines, so as to imagine the possibility of things growing alongside and materially intertwined with one another.

Michael Newman once asserted that “The mediums of art are concretions of time”, with each medium and each artwork serving to “delay, condense and spread-out time in their own way”[6]. In this exhibition, for example, we see the slow time of pulling a crayon across the tooth of an aluminium plate; the instant of photo-sensitive capture; and the brief passage of contact that occurs when printing plate and paper pass through the press together, joined momentarily in what Michael Rothenstein called an embrace[7].

However, it seems to me that we can go a step further than Newman and say that mediums do not just move time in different ways, they also harness and gather things that occur in time in particular ways too. Indexical traces of touch, for example, cohere differentially through the drawn, the printed, and the captured. Each means of contact leaves residues on the surface that evidence acts of attention, care, and even force. What arises in the intertwining of media are more than concretions of time, but also phenomenological questions of tactility and present-ness.

NOTES

[1.] The ‘body’ proposed here may be human, or indeed non-human.

[2.] Riccioli’s map, Almgestum Novum (published 1651), assigned poetic names for what were thought to be bodies of water on the Moon which remain in use today, including the Sea of Tranquillity.

[3.] Francis Place’s work Prospectus Australis (1676) from the series Vivarium Grenovicanum is held in the British Museum, London, where I have lived for the past five years.

[4.] In 1884, 22 countries voted to adopt the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian, making it the common zero of longitude and the standard of time reckoning throughout the world.

[5.] John Cotton was a British born naturalist who made studies of birds he encountered in Australia between 1844-1849.

[6.] Michael Newman, ‘The Marks, Traces, and Gestures of Drawing’ in Catherine de Zegher (ed.), The Stage of Drawing: Gesture and Act, London and New York 2003: p. 105

[7.] Michael Rothenstein quoted in Ruth Weisberg, ‘The Syntax of the Print: In Search of an Aesthetic Context.’ The Tamarind Papers: A Journal of the Fine Print 9, no. 2 (1986): p. 58.

—

Sea Sings, Lumen and Wings Realm

Works by Jo Darvall, Clare Humphries and Martin King

Print Council of Australia Gallery, Studio 2 Guild, 152 Sturt St, Southbank

1 – 22 September, 2023, OPENING RECEPTION: Thursday 1 September, 5-7pm

GALLERY HOURS Tues-Fri 10am-4pm

—

Join the PCA and become a member. You’ll get the fine-art quarterly print magazine Imprint, free promotion of your exhibitions, discounts on art materials and a range of other exclusive benefits.

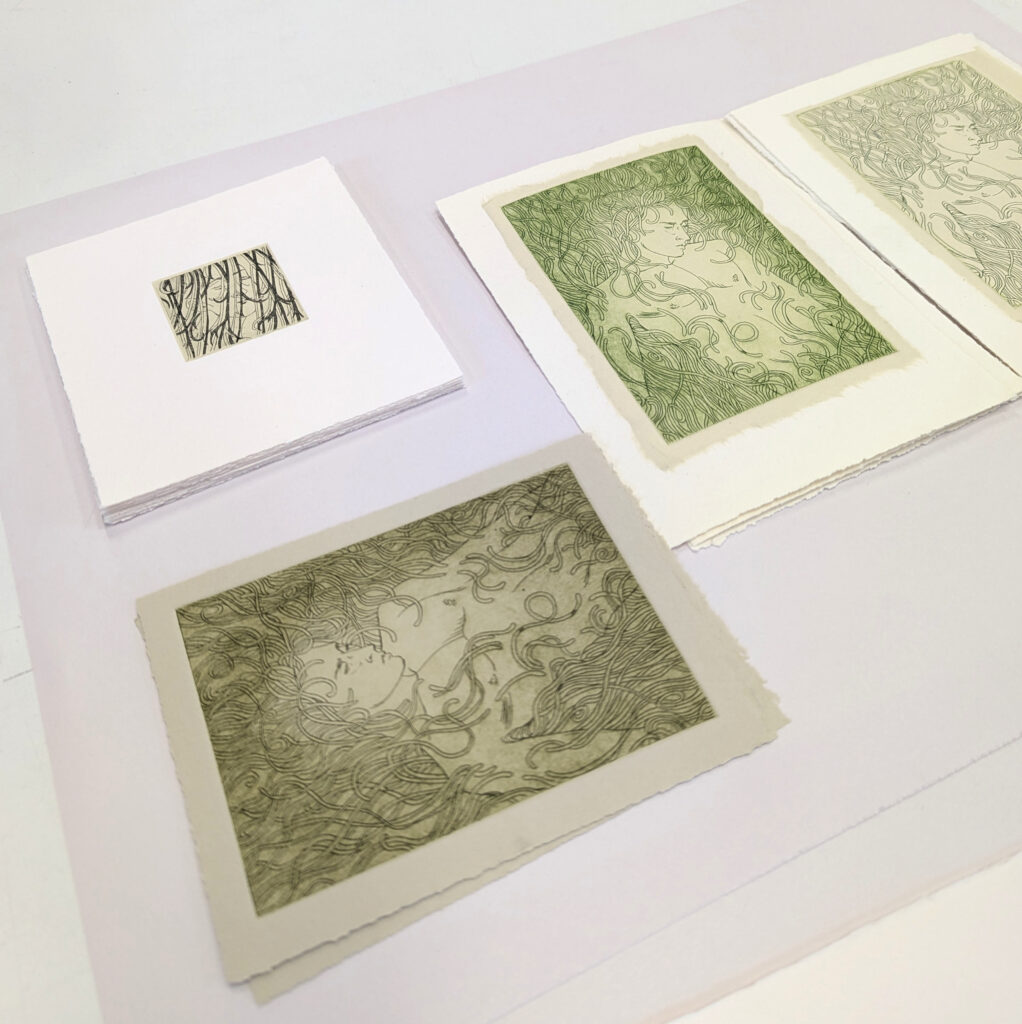

Main image, top:

Jo Darvall

Sea Sings & Winged Realm no 7, 2023

Unique state, multi-plate monoprint on Arches paper

56 x 75 cm

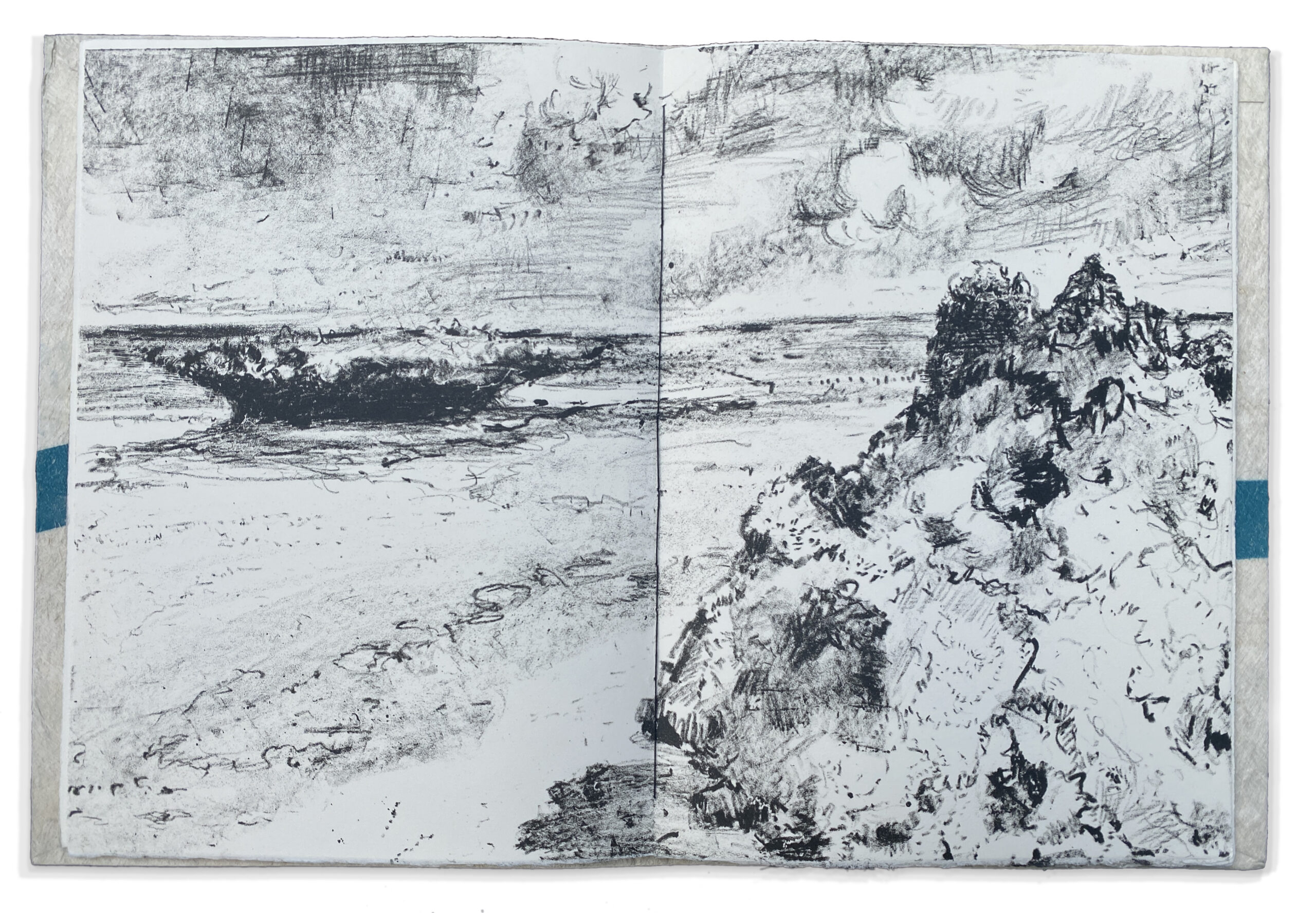

Below:

Jo Darvall

Ravuka Point, Yadua Fiji, detail from Hydrosphere, 2023

Artist book, lithographs hand-drawn by the artist, printed by Peter Lancaster & Emma Sattler at Lancaster Press Fiji, with Masi paper binding and poetry by Yan Toussaint

35 x 51.7 cm (page spread)

Below:

Clare Humphries

Perspectus Australis (with feet opposite), 2023

Ink and dry pigment on paper; hand-sanded reduction

linocut print with direct-trace drawing

44.5 x 112 cm (paper)

Below:

Clare Humphries

Seas of Delirium (South side up), 2023

Ink and dry pigment on paper; hand-sanded reduction

linocut print with direct-trace drawing

44.5 x 48.5cm (paper)

Below:

Martin King

pages from the diary of lost souls, 2022

Etching, drypoint, spitbite, photopolymer gravure, chine collé

100 x 80cm

Below:

Martin King

lighting the way for the journey of lost souls, 2022

Photopolymer gravure, chine collé

60 x 145cm